Architect: Safdie Architects

Location: São Paulo, Brazil

Opening: August, 2022

Continuing their work on curved-roof atriums, exemplified by the Jewel at Singapore’s Changi Airport, Safdie Architects has emulated the feeling of a tree canopy in São Paulo’s Albert Einstein Education and Research Center (AEERC). With state-of-the-art medical research facilities, the project connects to an existing hospital in the city’s Morumbi district.

The building will serve the needs of over 2,000 medical and nursing students, containing 40 classrooms—with programmatic flexibility—an auditorium, laboratories, and facilities to simulate examination and operating rooms. The building is organized around a tiered central atrium that houses a garden-like space, while also connecting the four primary floors of the building. The central court is shaded by a vaulted glass ceiling, with three structural domes spanning its length. Around the atrium, facilities are grouped in two wings, with the building’s structure embracing the sloping landscape of the 12,000-square-meter (129,167-square-foot) site.

The 3,800-square-meter (40,900-square-foot) ceiling was constructed from 1,854 glass panels, with minimal structural steel in order to reduce weight. The glass is barely reflective, as the architects did not want strong reflections to impact the surrounding environment. It was designed with extensive digital modeling. As Safdie Architects partner Sean Scensor and senior associate Isaac Safdie explained, the “aim was to simulate the effect of being outdoors, under the canopy of trees, on a beautiful day with a clear view of the sky above.”

Working between offices in São Paulo, London, and Boston, and collaborating with mechanical and environmental engineers, horticulturalists, and landscape architects, the team at Safdie led the modeling of environmental factors that led to the final design and material decisions. Shading was a delicate balance; as Safdie and Scensor explained, they needed to provide enough light for the plants, while limiting the glare of direct sunlight and also keeping electricity usage to a minimum.

In order to sustain the garden, the model tracked optimum light levels—20,000 lux for 1,200 hours per year—evapotranspiration rates of the plants, and determined a maximum temperature of 24 degrees celsius (75 degrees fahrenheit) and a maximum relative humidity of 50 percent. With climate data from São Paulo, the team used ray tracing software to model the full range of daylight conditions. Based on this data, the architects selected insulated laminated glass with low emissivity solar coating, high visible light transmittance, and a neutral color. The team also used computational fluid dynamic modeling to “map heat and humidity in the space over time… maintaining comfort for both people and plants,” said Safdie and Scensor.

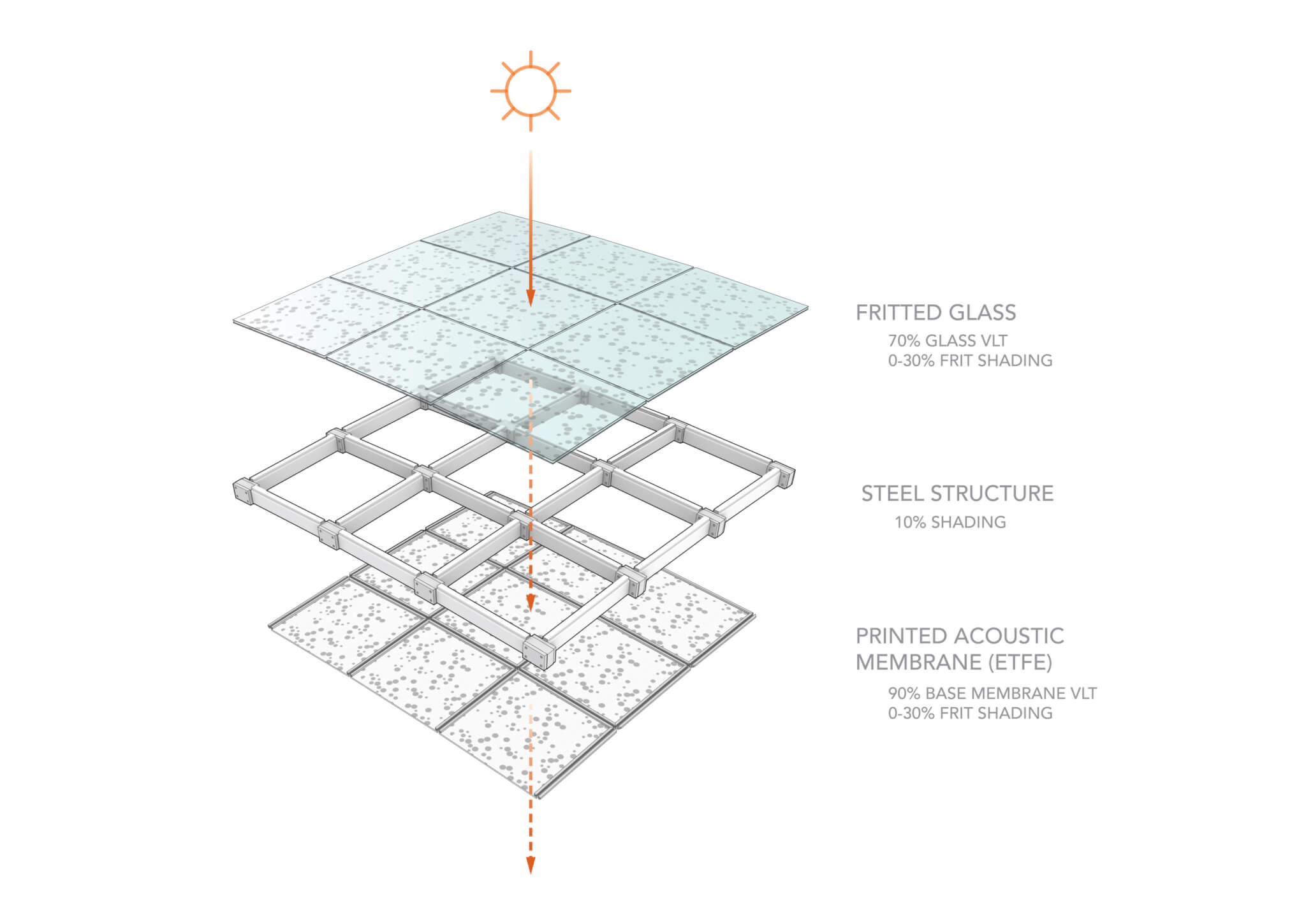

Safdie and Scensor further explained that the model presented a challenge in that it “could not fully model the beneficial effect of the tree canopy…requiring special interpolation and interpretation of the results.” The final design of the roof was formed of an outer layer of fritted glass, attached to a steel structure, and an inner layer of a printed acoustic membrane. The outer layer of fritter glass was fabricated with a pattern of translucent ceramic dots, which act as a solar shading mechanism. The inner membrane layer was micro-perforated to absorb sound, and also printed with a pattern of translucent dots for solar shading, though these dots also glow in sunlight. The dots were arranged to be denser as they approached the east and west ends of the building, effectively shading the sun at low angles. The dual layers of dots filter the dappled light, giving the intended effect of the tree canopy.

Sun shading was also a primary consideration on the faces of the building, most of which contain floor-to-ceiling glass. The building is tiered on alternating floors, with the floors that are set back shaded by the overhanging floor above. The floors that are not shaded by the overhang were wrapped in a polymer resin brise-soleil, shading them while still allowing for views of the neighborhood. As Safdie and Scensor explained, the design team “primarily used passive solar design principles,” placing 40 percent of the program below street level in addition to the daylight from the atrium, which reaches lower levels. The architects opted for triple silver-coated glass, maximizing shading performance and reducing the need for electricity usage during the day.

Using digital modeling, scaled physical models, and full-size mock ups, the design team studied the louvers of the brise-soleil to optimize shading. By spacing the louvers 37 centimeters (14 inches) apart, and tilting them 45 degrees, they were able to optimize shading without blocking views of the exterior. The diagonal louvers were installed on the east- and west-facing facades to shade morning and afternoon sunlight, while the louvers on the north were left horizontal to shade direct sunlight midday.

The louvers were fabricated with polymer resin over concrete, metal, and fiberglass options, for its light weight, tensile strength, and precise tolerances. The pine wood color of the resin was customized to minimize cleaning, but also establishes visual continuity with wood used in the interior. The shape was also customized, which Safdie and Scensor described as “winglike,” diffusing light by bouncing it between louvers. Rooms are also equipped with operable solar and blackout shades, allowing for adjustment based on occupant needs.

While the design attempted to control environmental needs as much as possible, São Paulo’s climate did pose challenges during the construction process. The rainy season prolonged the site excavation, but the design team was able to assemble full-scale mock ups on a nearby lot. Representing each significant component of the building, including a full-size classroom, materials and design features were demonstrated to the client. Collaborative work with tradespersons, particularly in custom assembly, was key to saving time and improving quality control.

Refining the exposed concrete was a complex process that required the design team to work with a number of subcontractors to evaluate the formwork, mix, curing time, and sealers that were locally available. Safdie worked with Perkins&Will’s São Paulo office—the Architect of Record on the job—and the contractor, Racional, to specify domestic suppliers and manufacturers on a range of materials, saving costs by reducing the quantity of imported materials.

The design team worked closely with Seele on the structural design, fabrication, and installation supervision of the glass ceiling. Safdie previously worked with the firm on the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), and encouraged the client to bring on Seele during early phases of the design process, streamlining materials selection, cost, and constructability. The contractors and client were able to tour both the USIP and the Jewel to understand the need for long-term maintenance of the skylight, and to learn from the past construction processes.

Project Specifications

- Architect: Safdie Architects

- Location: São Paulo, Brazil

- Opening: August, 2022

- Programmer, Interior Planner, and Executive Architect: Perkins&Will

- Landscape Architect: Isabel Duprat

- Skylight Sub-Contractor: Seele

- Structural Engineer: Thornton Tomasetti, Avila Engenharia, BRZ Experts

- Facade: Thornton Tomasetti, Crescencio

- Environmental: Atelier Ten, Ca2

- Horticulture: Sue Minter

- General Contractor: Racional Engenharia

- Exposed Concrete Beams: Peri

- Glazing: Schüco

- Glazing Installation: Luxalum

- Brise-Soleil: Lure