With bigwigs and celebs jetting away at last from Scotland’s global climate summit, what else is afoot in the city of Glasgow?

The famous 1909 Glasgow School of Art by Charles Rennie Mackintosh has not been rebuilt after its near destruction after two fires in 2014 and 2018. The cause of the latter conflagration remains elusive. While its restoration may be years off, the good news is that in October, leaders of the school agreed that “faithful reinstatement” would be the preferred strategy for rebuilding.

The other options were to build a new building altogether, or a hybrid consisting of new structure inserted into what can be saved of the original structure.

Faithful reinstatement leans, as I understand it, more toward replication among the various synonyms for restoration. Many modernist architects and academics have pushed since 2018 for the school to lean toward new construction or some sort of hybrid. They assert, dubiously, that since Mackintosh was creative, the most “creative” rebuilding strategy would best honor his innovative nature. So the best strategy would be that which is the farthest from rebuilding the Mack (its local nickname) as originally designed – failing to notice that such a strategy would also precipitate flight among potential donors to the building’s salvation.

The most stringent definition of restoration would favor using as much of the remaining structure as safely possible while fabricating damaged or destroyed structures, features and embellishments with Mackintosh’s original designs as templates, with materials as close as possible to the original. Extensive archival drawings and photographs, assembled over the years, enable artisans to replicate the architect’s quirks with considerable confidence.

Architects Journal adds detail about long-revered spaces within the building that are more or less lost but could be devotedly replicated:

Iconic spaces, such as the library, board room, director’s office, Mackintosh Room, lecture theatre, Studio 58, the Hen Run, loggia, museum and Studio 11 will be reinstated together with all the other spaces, including studios.

But some observers have been pushing against that reasonable strategy. Among the most persistent is architect Alan Dunlop, whose opinion seems to appear with deadening regularity wherever rebuilding GSA is discussed. Last year, after desire for its restoration seemed to gain the upper hand, Dunlap tried to retwist the debate in his own direction:

I think the narrative around the future of the building has changed, with the emphasis now on restoration rather than replication of the original school. In other words, we should save what’s left of the building and put in a modern insertion.

He nudges and declaims, as if his kooky preferences might somehow gain force if repeated often enough. Since even the recent decision to faithfully reinstate the Mack is still subject to continued obsessive official analysis and reassessment, Dunlop might win in the end. But since the October decision, he seems to have resigned himself to the prevailing restoration strategy. No doubt he’ll be lying in wait in case things turn south, as often happens in cases of extreme bureaucratic sclerosis. No one expects the building to reopen before 2028 at the earliest.

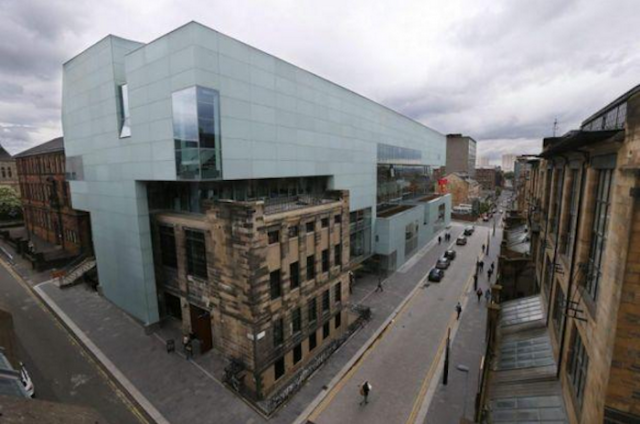

My preferred alternative would be to not only rebuild the original as faithfully as possible but, in addition, to demolish the school’s recently built Seona Reid building by Steven Holl directly across Renfrew Street from Mackintosh’s original structure. What a horror! (See below.) But, of course, that will not happen. Which does not mean that it should not happen. Here is a quote from the opening of Observer critic Rowan Moore’s review of it, which places the building – and all others of its ilk – in proper perspective:

“Have you heard of the artist James Turrell?” asks Chris McVoy, partner in Steven Holl Architects of New York, and inside me something dies. When architects mention Turrell, it means that they have seen his installations and think that, because like him they play with white walls and light, they can make something as mesmerising. However valid their work in other ways, they can’t. It is like thinking that any painting of yellow flowers is a Van Gogh.

(As mesmerising as what? one might nevertheless ask.)

Like so many other cities in Europe, including London and now Paris, Glasgow has tried to commit suicide via modern architecture. Luckily, Europe’s stock of historical fabric is so intact that it takes a lot of modern architecture to ruin. Most American cities once had such strength but do not any longer, and have not for a long time. (Providence still does.) In deciding to “faithfully reinstate” its famous school of art, Glasgow seems to recognize (as the leaders of Providence do not) what they must do to avoid the fate of American cities like Houston. (My advice: city planners everywhere should set aside a sandbox for the modernists.)

One building material that’s growing as it increases in availability. Plastic. People will criticize, but plastic is virtually ubiquitous and lack of what to do with the waste….

An intersection in front of Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall is set to test municipal plastic asphalt

https://images.adsttc.com/media/images/5264/acf3/e8e4/4ef4/c200/021b/large_jpg/wdch_built_01_gp_pr.jpg?1382329540

Now the very plastic that once littered our streets is gonna be used to make em. the plastic asphalt is actually more effective than regular asphalt, reportedly being six to seven times stronger, as well as being much more cost-efficient.

LikeLike

Ahh glasgow, a town so famous, they named a sinister act of bodily harm after it…

LikeLike