Editor’s note: Here is a post from December 2013, almost a decade ago, shortly after the Providence Journal booted my Journal blog from its roster of staff-written web logs, which is where the word “blog” comes from. I used to write two or three of these per day, even while I was also writing editorials and my weekly column. Maybe that is why the Journal put a stop to it.

***

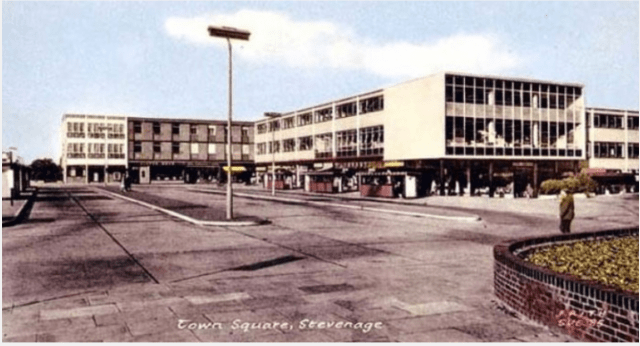

The title of this post harks back to one from this blog’s Providence Journal days, when I linked to a long piece in Metropolis magazine by Michael Mehaffy and Nikos Salingaros, and then did a column about it called “How modern architecture got square.” Now a piece by Robert Adam, the British classical architect, approaches the same issue from a different direction. It is called “The Institutionalization of Modernism,” in his blog at Building magazine, published in the U.K.

[Adam’s article is here.]

The piece follows Adam as he rifles through a series of official British planning documents going back years, which trace the growth of language in planning regulations there that force planning officials to favor modern rather than traditional architecture.

Planners in Britain must adhere to national planning policy summed up in official documents since passage of the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947. The latest version of the document, which he describes as “quite good,” states: “Planning policies and decisions should not attempt to impose architectural styles.” Maybe so, but a lot of official policy in prior years had similar language yet nevertheless favored or even mandated modernist styles, whether the wording of the rule stated so expressly or hinted it. (In bureaucracies, hints are often hazardous for lower-level officials to ignore.)

One example comes from planning regulations in two historic towns, Winchester and Chester. In Winchester, planners must abide by language that reads: “New development should complement but not seek to mimic existing development and should be of its time.” The first part sounds sensible to the average citizen, but the code words of “mimic” and “of its time” suggest very straightforwardly to planners that modernism is to be favored. Regulations in Chester beat even less around the bush: “The boldest and most successful designs are those which clearly express the ethos to which they relate, and do not refer to the language of earlier periods.”

In his piece, Adam describes planning language widespread in planning documents that may seem unobjectionable to many but is interpreted with great specificity as pooh-poohing new traditional designs by those charged with carrying out the law.

Adam concludes: “This is all part of the creeping institutionalisation of modernism. For half a century it has been the style of the architectural establishment. It is now becoming the style of the bureaucrats.” That’s bad news, but Adam hopes that Britons who want to rescue their built environment from modernism will send him examples from their jurisdictions that can be used to illustrate today’s reality and thereby encourage top planning authorities to even the playing field.

“I have spoken to the government’s chief planning officer,” advises Adam in a note to readers who want to join in the fun, “and he [is willing] to receive [letters] on the subject. [They] will need to be very cool and factual.” Well, readers, I guess that means it’s up to you!

Please send any examples to Robert Adam at adam.pightle@GMAIL.COM.

***

[I believe this is Robert Adam’s current email address; the one originally published with this column, robertadam@adamarchitecture.com, no longer works. I wonder whether Mr. Adam will enjoy receiving examples drawn from contemporary planning documents.]

The modernists relied on personalities who were instrumental in imposing modernism on society. Bureaucrats don’t have much personality, they are followers. So the traditionalist scene needs personalities too, if necessary of a somewhat dictatorial type…, endless reasoning and debating, appeals to rationality, policies, etc, it is by far not enough (it’s too modern..). Of course, strong personalities in combination with the vote of the public, not because the public has a good taste, but the public does tend towards conservatism.

LikeLike

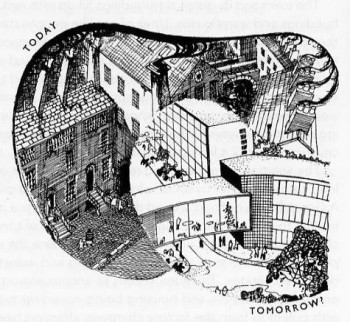

It’s in the ironic nature of futuristic architecture that the closer you get to the putative “Future” arrival time, the more these icons look like yesterday’s tomorrow.

Never the less still want see my floating cities

https://images-wixmp-ed30a86b8c4ca887773594c2.wixmp.com/f/4c4a8087-ea04-41a7-90fb-6172ffa781a7/d3cq32a-c94dc3e6-b021-4e05-9534-a5f6af293cd6.jpg/v1/fill/w_1000,h_706,q_75,strp/floating_city_by_javieralcalde_d3cq32a-fullview.jpg?token=eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLCJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiJ9.eyJzdWIiOiJ1cm46YXBwOjdlMGQxODg5ODIyNjQzNzNhNWYwZDQxNWVhMGQyNmUwIiwiaXNzIjoidXJuOmFwcDo3ZTBkMTg4OTgyMjY0MzczYTVmMGQ0MTVlYTBkMjZlMCIsIm9iaiI6W1t7ImhlaWdodCI6Ijw9NzA2IiwicGF0aCI6IlwvZlwvNGM0YTgwODctZWEwNC00MWE3LTkwZmItNjE3MmZmYTc4MWE3XC9kM2NxMzJhLWM5NGRjM2U2LWIwMjEtNGUwNS05NTM0LWE1ZjZhZjI5M2NkNi5qcGciLCJ3aWR0aCI6Ijw9MTAwMCJ9XV0sImF1ZCI6WyJ1cm46c2VydmljZTppbWFnZS5vcGVyYXRpb25zIl19.KWgX8Uw7NlMhqgaht6PhDrPJuHH2c-3yJc1pLSfbmuQ

LikeLike

Actually The Sydney Opera House looks like something which could evolve in the deep oceans, and various other structures in terms of colour or shape look like they could be, if not of primordial origin, built by primitives, if only they had the technology.

LikeLike

The way I am seeing certain modern buildings is that they are sculptures blown up large for habitation. Often these art pieces are problematical for humans to live , work , educate IN.

My school in Connecticut selected a few sculptures safe for children to play in and on from

a show in Central Park, NYC. The children enjoyed playing with them, but then the rain

came. What were we thinking?

LikeLike