This article was written by Burgess Brown. Healthy Materials Lab is a design research lab at Parsons School of Design with a mission to place health at the center of every design decision. HML is changing the future of the built environment by creating resources for designers, architects, teachers, and students to make healthier places for all people to live. Check out their podcast, Trace Material.

This article is Part II of a three-part series on the hazards of vinyl flooring.

- Part I explores “dirty climate secret” behind the popular material and shares some healthier, affordable alternatives.

- Part II, this article, considers the long history of worker endangerment by the vinyl industry and how this legacy continues in China today.

Part One: Import Limbo

Warehouses and docks at the Port of New York and New Jersey are filled to the brim with shipping containers full of products like solar panels, textiles and flooring. These containers are stuck in import limbo. The bottleneck has had a particularly dramatic impact on the booming vinyl flooring industry as hundreds of millions of dollars worth of “luxury” vinyl tile collects dust or is returned to sender. They are being meticulously inspected by Customs and Border Protection–part of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act recently passed by the federal government. Customs is looking for products whose life cycles begin in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR).

This region has become the center of human rights abuses against Uyghurs [pronounced WEE-gur], an ethnic minority group indigenous to Xinjiang. The XUAR is an industrial hub for electronics, pharmaceuticals, apparel and technology fueled by state-sponsored forced labor of Uyghurs. A recent report called “Built on Repression” from the Helena Kennedy Centre for International Justice at Sheffield Hallam University and Materials Research L3C highlights a new and concerning industry in the region: PVC production. According to the report, The Uyghur Region has become a world leader in the production of PVC plastics in recent years. The seven PVC manufacturers in the XUAR produce 10% of the world’s PVC. China, as a whole supplies 63% of U.S. vinyl flooring.

There are many products coming out of the XUAR that are manufactured using forced labor, but none compare to PVC flooring when it comes to human and environmental health effects. According to “Built on Repression” author Jim Vallette, “There’s nothing like it on Earth in the combination of climate and toxic pollution. And workers are living there 24/7.”

Part 2: A History of Abuse

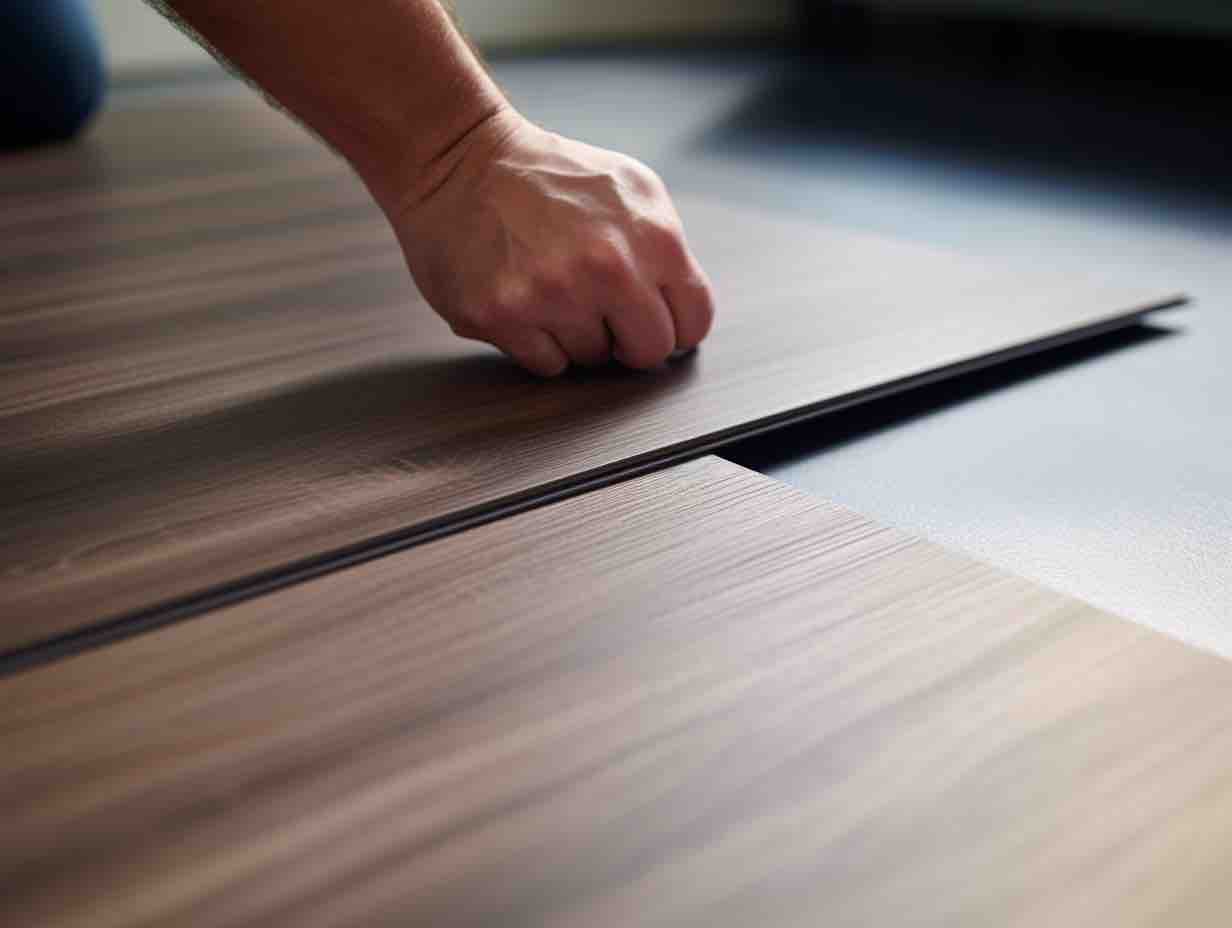

Image generated by Architizer using Midjourney

The toxicity of vinyl production has been a well documented fact for decades and labor abuses have been part and parcel of the industry from the start. As the chemical industry began ramping up PVC production in the ‘60s and 70’s, laying the groundwork for its eventual widespread use, they discovered that vinyl chloride monomer (the building block of PVC) was a carcinogen. They chose to hide these findings from the public and their workers. The story of this global coverup is revealed in the groundbreaking book, “Deceit and Denial: The Deadly Politics of Industrial Pollution” by historians Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner. By the 1970s, PVC workers across the U.S. contracted a rare form of liver cancer and the pattern forced industry leaders to go public about the dangers they had kept hidden. For more on this story, take a listen to the episode of HML’s podcast, Trace Material, entitled “The House of Documents” that features interviews with Gerald Markowitz and other key players that pulled back the curtain on the early PVC industry.

While working conditions have improved in the U.S.,there is unfortunately no safe way to produce, use or dispose of PVC. Workers, residents and fenceline communities continue to be exposed to cancer-causing chemicals. In China, the situation is even more dire. Chinese makers of PVC use an outdated and extremely toxic production method that is far more dangerous to people and the planet. The Uyghur Region has become a locus of PVC production in part because of the plentiful coal resources in the region. Factories are set up adjacent to coal mines and use coal fired power plants as an energy source. They incorporate an incredibly toxic mercury-based catalyst in the production process. This is one of the last remaining places on the planet where this method of production is utilized. The plants in the XUAR will release an “estimated 49 million tons of global warming gasses, each producing more than any other similar plant” and the estimated air emissions are equal to more than half of the air releases of mercury (14.8 tons) reported in all manufacturing in all of the United States in 2020, according to the “Built on Repression” report. At grave cost to our planet and bodies, XUAR-manufactured PVC and the products made from it have become absurdly inexpensive. U.S. manufactures are unable to compete and Chinese PVC has become the most common material in all new floors sold in the U.S.

Global demand for luxury vinyl tile has meant massive growth for a toxic industry in China. To keep up with demand, the government of the People’s Republic of China has instigated a sweeping program of forced labor in the XUAR. One of the primary methods used by the government are “labor transfer” programs. According to the “Built on Repression” report, “Through state agency labor recruiters, the PRC government compels people to be transferred to farms and factories across the Uyghur Region. Others have been ‘transferred’ thousands of miles into the interior of China to work in factories. The XUAR government estimates that it has deployed these programs 2.6 million times.”

The report states that refusal to participate in these programs can be considered “a sign of religious extremism and punishable with internment or prison in the Uyghur region.” Uyghurs are effectively unable to refuse a “transfer” or leave a job assigned to them. Millions have been separated from their families in what is tantamount to human trafficking and enslavement.

Part 3: New Cancer Alleys

Image generated by Architizer using Midjourney

The U.S. government has responded to these atrocities by passing the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. The act effectively bans all imports whose origin can be traced to the Uyghur region. Tracing the origins of LVT has become increasingly difficult as China has made their supply chains even more complicated and opaque. PVC resins created in the XUAR are shipped to Thailand or Vietnam to be turned into flooring before export. The U.S. flooring industry has responded by returning as much production to the U.S. as possible. But, without forced labor and cheap coal, manufacturers can’t match price and capacity demands. While the steps to divest from an industry propped up by forced labor are certainly positive, ramping up domestic production of PVC brings risks to the health of U.S. workers and communities living near the factories. The heart of plastics production in the U.S. sits along the Mississippi River in Louisiana. The area has become known as Cancer Alley because residents are about 50 times more at risk of developing cancer than the average American. As the plastics industry vacates China and returns to the U.S., it’s building new cancer alleys in Ohio, West Virginia and Pennsylvania. Our demand for inexpensive flooring outsourced cancer, now that demand is bringing cancer home.

So what should be done? According to Gerald Markowitz, we need to stop using PVC altogether. Here are his suggestions:

“The United States should begin eliminating PVC by categories of use. Legislation has been floated in California to prohibit PVC in food packaging — a ban that could be expanded to other nonessential needs. Though PVC is inexpensive, it is replaceable in most cases. Alternatives include glass, ceramics, linoleum, polyesters and more.

Also, discarded PVC should be labeled a hazardous waste. The designation would put the burden on users for its safe storage, transportation and disposal, creating an incentive to accelerate its elimination.”

We at Healthy Materials Lab agree. LVT is durable, easy to install and maintain, inexpensive and toxic. Its low purchase price is outweighed by a massive cost to human and planetary health. By refusing to specify LVT, architects and designers act as advocates on behalf of the health of all communities. Attractive, affordable, healthier flooring products exist. Take a look at part one of this series (or the healthy flooring materials collection on our website) for a list of some alternatives that include healthy materials like cork, hempwood and linoleum. And, stay tuned for the final installment of the series where we will take a closer look at what happens to LVT at the end of its life and the limits of its circularity.

The judging process for Architizer's 12th Annual A+Awards is now away. Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter to receive updates about Public Voting, and stay tuned for winners announcements later this spring.