Everyone knows about Root’s famous chamfer of the corner of the Monadock, but I have only recently understood a much more subtle detail on the part of Root in the Monadnock. It took me almost 50 years to see it, let alone understand it, but I hope I have it figured out. There is an old saying among artists, sometimes you do something for yourself, and if even one person finds/appreciates it, it was worth the doing. I think this detail I am going to discuss is just one such detail.

In his 1973 biography of Root, Donald Hoffmann included this cryptic sentence on p. 166: “The upper framing members of the sash windows were rounded at the ends, and the broad frames of the second-story windows were gently bowed to echo in the vertical plane the bowing of the bays above.” He included no photos of this detail, so I assume like most people, I read the sentence without digesting its importance. Recently as I was looking at a number of detail photos of the lower two floors, I caught the curve in the corners of the windows under the bays: with this detail was Root showing how the three-dimensional curve of the bays above was first emerging in two-dimensions in the window frames located immediately below the first bay in the third story? As was the case with the chamfered corner, Root was again playing with optical illusion. If one looks from just the right angle, (above left photo) the curved frame makes the glass look like it is gently bowing out, setting up the curved bay above.

Apparently, Root used this detail in the first-floor windows as well, as the pre-restoration photo above does match the restored version. Here my opinion differs from Root, for I argue that with the first-floor windows also curved, Root blew a chance to show the growth of the curved bay from a simple rectilinear void on the ground-floor to a transitional curved frame in the second-story to the full-grown curved bay in the upper floors. I would like to know if Root also used the rounded frames in the single windows he cut into the masonry piers between the bays. I hope he didn’t because if he did, it negates this idea of showing the growth of the curved bay from ground floor to its full emergence above, and my hypothesis of Root’s emergence of the curved bays is simply a post-rationalization. (If you have the chance, when you walk by the Monadnock, take a picture or two of the single window frames and forward to me: thanks!) I owe acknowledgements to a number of my followers (especially friend and former student Tom Lee) who took the time to shoot close-ups of these windows so I could get a better grasp of their detailing and share them with you.

Let’s take a moment to put these curved corners into perspective. Hopefully, this motif should jog your memory as an Art Nouveau detail. I include images of two of the better examples of this: Victor Horta’s house (1898) and Antoni Gaudi’s Casa Batlló (1906).

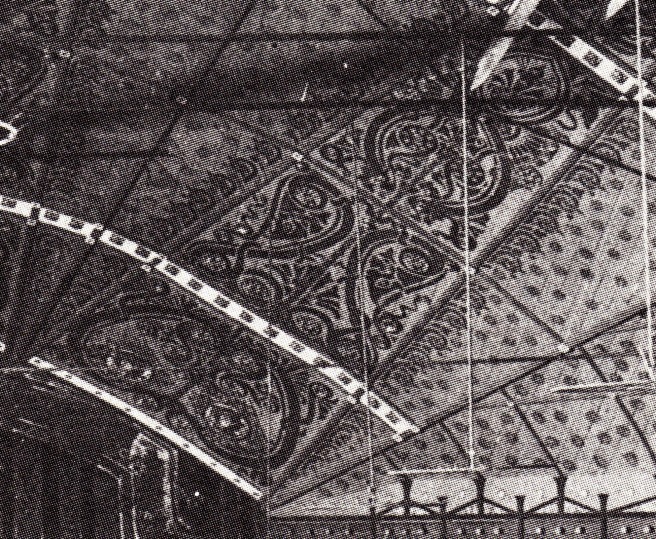

Root’s curved window detail is another Chicago School example, in conjunction with Louis Sullivan’s proto-Art Nouveau stenciling in the 1885 Chicago Opera Festival retrofit of the Interstate Exposition Center (v.4, sec. 10.19) as well as his interior details in the Auditorium, that gives evidence to the contemporary emergence of a modern style of architecture in Chicago that paralleled that in Europe.