The latest edition of “Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture” — a stunning, hardbound book celebrating the most inspiring contemporary architecture from around the globe — is now available. Order your copy today.

Épater la bourgeoisie! This was the rallying cry of the French Decadent poets of the late 19th century. In English, it translates to “Shock the bourgeoisie!” and suggests that the first duty of the artist is to provoke the audience by challenging their notions of what is beautiful, reasonable, or morally permissible.

In architecture, this attitude has a long provenance. The early modernists knew their mechanistic rationalism upset the bourgeoisie, who felt attached to the cozy trappings of tradition. And when modernism became the preferred aesthetic of the bourgeoisie, the deconstructivists took up the mantle of the avant-garde, creating buildings that spurned norms like wholeness, symmetry and harmony.

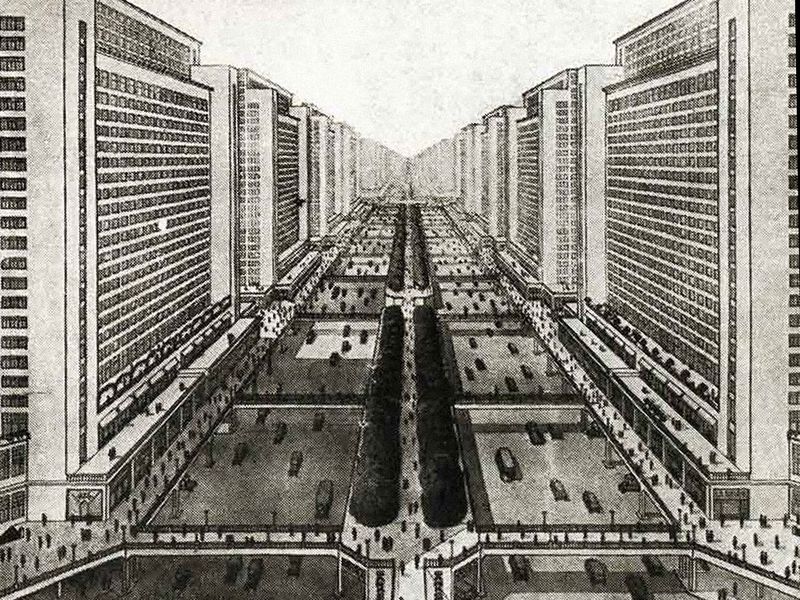

“The early modernists knew their mechanistic rationalism upset the bourgeoisie, who felt attached to the cozy trappings of tradition.” Le Corbusier was one modernist who relished his power to shock, especially with his Functionalist utopias like the “Radiant City.”

The deconstructivist architect Peter Eisenman put this perspective best during a debate with the traditionalist Christopher Alexander: “If we make people so comfortable in these nice little structures, we might lull them into thinking everything’s alright… when it isn’t.” For Eisenman, architecture must offer a challenge to the status quo, lest it reify unjust social relations by giving them a veneer of rationality and balance.

In the early part of his career, fellow deconstructivist Frank Gehry seemed to have sympathy for Eisenman’s point of view. The home he designed for his family in Santa Monica in 1978 was a direct rebuke to the surrounding neighborhood — a cookie cutter California suburb reminiscent of the Pasadena neighborhood depicted scathingly in Mike Nichols’ 1967 film, The Graduate.

Instead of tearing down the tasteful Dutch colonial house that once stood on the property, Gehry built a new house around the old one, a jagged fortress of metal, plywood, and glass. “The neighbors got really pissed off,” Gehry told Dezeen with pride in 2021. Eisenman would have likely approved, as would Baudelaire, Duchamp, Lou Reed and every other artist who took it as their mission to shock the bourgeoisie.

Frank Gehry infuriated his neighbors with the radical design of his residence.

Today, however, Gehry is far from an outsider. In fact, he is probably the world’s most famous living architect. In 2022, the wealthy denizens of Santa Monica would not be scandalized to live next to him. To the contrary, he is likely on the short list of architects they would think of if they decide to donate a new wing to their alma mater’s arts center. Gehry has seemingly adjusted to this new status, telling Dezeen in 2021 that “I don’t antagonize. I don’t try that. That’s not my way.”

And yet, it is hard to take this comment at face value. In this same interview, which concerned the opening of the Luma Arles tower, Gehry responded scornfully to critics who questioned the building’s environmental specs and its relationship to its historic setting in the city of Arles. “We fit into [the context],” he said. “But I can’t explain it. I respond to every fucking detail of the time we’re in with the people we live with, in this place. You know, I believe that’s the most important thing to do. To live in the place and time you are in and what the issue is, you know, even with these fucking masks.” At this last point, he gestured to the facemask that he had worn into the interview. He did not, it must be noted, go on to explain how he had been taking Covid-19 into account in his recent work.

Some have questioned whether Gehry’s Luma Arles Tower blends in with the surrounding city. At 183 feet (56 meters), it is by far the tallest structure in Arles.

Profanity aside, these comments revealed a lot about Gehry’s attitude toward his perceived public — or, toward the bourgeoisie. For one, he is unapologetic. The 183 foot (56-meter), twisting, steel-clad Luma Arles tower radically changed the visual identity of the city, which is well-known for its Roman ruins and connection to art history. (It was here — well, near here — that Van Gogh painted his famous Starry Night, gazing out from his asylum window, and many other painters, including Picasso and Gauguin, were similarly drawn to the city’s delicate southern light). And yet Gehry does not feel he needs to address the concerns of those who miss the old Arles. These people, one imagines, are motivated by nostalgia, a reactionary sensibility that deserves no sympathy. When Gehry says he “can’t explain” his building, he implies that he shouldn’t have to.

This was not the first time that Gehry lashed out at bourgeois tastes. In a 2014 press conference in Spain, Gehry gave the middle finger to a reporter who asked him what he said to critics who said his buildings were too flashy, privileging form over function. “Let me tell you one thing,” he said. “In the world we live in, 98 percent of what gets built and designed today is pure shit. There’s no sense of design nor respect for humanity or anything. They’re bad buildings and that’s it.”

Detail of the Luma Arles tower. The jagged steel panels of the facade are meant to evoke Van Gogh’s rough brushwork.

Gehry later blamed jet lag on the outburst, but one imagines there was more than a grain of honesty in these comments. Gehry sees himself as an artist, and as such, he invites the scorn of the public who just don’t understand. He even wears it as a badge of honor. In 2007, Gehry was seen wearing a t-shirt that said “Fuck Frank Gehry” across the front. Asked about it by the New Yorker, Gehry explained that he often saw these t-shirts on the streets of Bilbao when his Guggenheim Bilbao was under construction. Instead of getting offended, Gehry had his team order a whole box of the shirts.

“You know, when Bilbao was presented publicly, there was a candlelight vigil against me.” Gehry explained. “And then there was a thing in a Spanish paper saying, ‘Kill the American Architect.’ That was scary. So I stood beside the President every time there was an event. I figured, if they’re gonna kill me . . . Anyway, once the building was built, I could live there for free. And the same thing with Disney Hall — when it was first shown they called it broken crockery, and now everybody thinks it’s great. So it takes a while. The little building on the West Side Highway, in New York? A few months ago, everybody was telling me how horrible it is, and now they like it.”

The IAC Building, Gehry’s “little building on the West Side Highway,” still divides New Yorkers.

The public, it seems, doesn’t know what’s good for it. It takes an architect – perhaps a starchitect – to show them the way.

Frank Gehry has made tremendous contributions to architecture in his six decade career. Many of his buildings, including the Guggenheim Bilbao, 8 Spruce Street, and Fondation Louis Vuitton, are among my personal favorites. At his best, he adds movement and dynamism to urban landscapes dominated by severe right angles and interchangeable steel and glass towers. But is the Luma Arles Tower Gehry at his best? And does the public have a right to weigh in? In the war between architecture and the public, does the public necessarily represent the reactionary side of the debate?

“At his best, Gehry adds movement and dynamism to urban landscapes.” The Fondation Louis Vuitton in the Bois de Boulogne in Paris has an ethereal, weightless quality.

There is a lot of money wrapped up in architecture, especially the high profile architecture that Gehry builds. Such buildings can also have a massive impact on the surrounding community — they’re not merely design objects. While some objections to Gehry’s buildings might be rooted in aesthetic conservatism, others have more to do with gentrification, labor issues and the environment. But these discussions are obscured by Gehry’s framing, which posits avant garde architects on the one side and a dull, unimaginative public on the other. In the 2020s, it is worth asking what radical design, taken by itself, really accomplishes. Are our cities strongholds of traditionalism crying out for deconstruction? Or is this, perhaps, yesterday’s battle?

The latest edition of “Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture” — a stunning, hardbound book celebrating the most inspiring contemporary architecture from around the globe — is now available. Order your copy today.