Five days after the laying of the cornerstone for the Woman’s Temple, a much grander ceremony on November 6, 1890, preceded the laying of the cornerstone for the 302’-1” Masonic Temple, for there was no more important building for such a ceremony. Mayor DeWitt C. Creiger, past Grand Master of the Illinois State Lodge, led a procession to the site of four thousand Masons, including those who held the all-important 33° Scottish Rite, dressed in black clothes to set-off their white aprons. The project was the idea of Norman T. Gassette, the Grandmaster of the Chicago Lodge, who most likely planned it as a response to the Minneapolis Lodge’s recently completed huge, 8-story building designed by Long & Kees, the newest and largest Temple in the Midwest. (I have not uncovered any evidence that either Root or Burnham were Masons.)

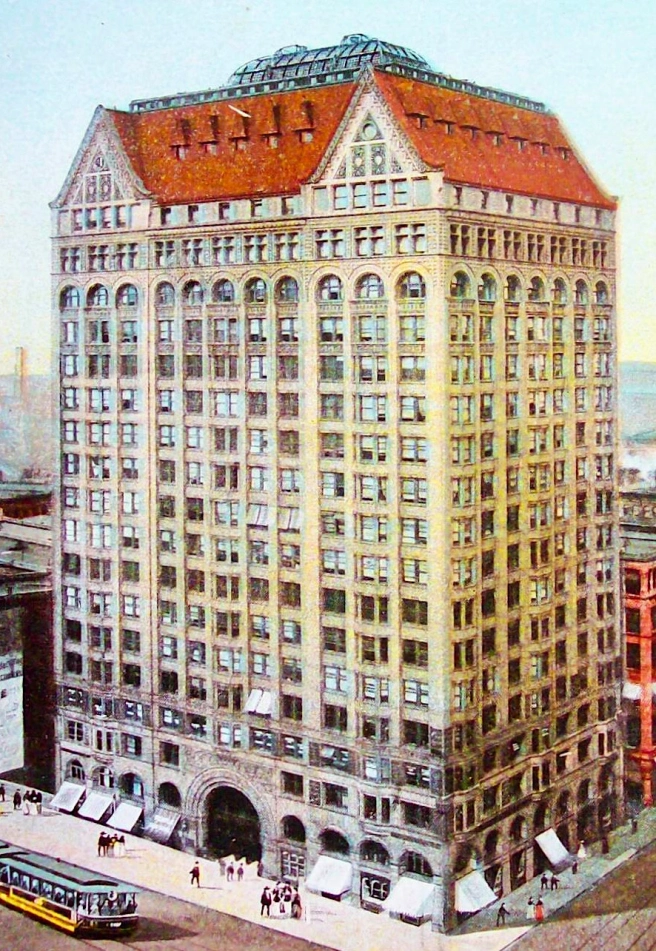

The Chicago Lodge had outgrown its rooms that it had rented in Richardson’s American Express Building since 1884, and Gassette appreciated the potential publicity that could be gained for the organization if Chicago would win the contest for the 1892 Fair. In anticipation of Chicago’s victory, the lodge bought the property at the northeast corner of State and Randolph in January 1890 and announced that it was planning to build a 12-story building that would contain the headquarters of the Illinois and Chicago orders, as well as an 850-room European-style Hotel. The Chicago Tribune reported that the new building would “honor Masonry, much as the Auditorium (that was still receiving its final finishing touches) has honored its promoters.” It was not at all odd that the report had mentioned both the planned Temple and the Auditorium (with its 17-story tower) in the same article, for the Mason’s planned building grew in height to 15 stories in February 1890, and then to 18 stories in July, when Inland Architect noted the real objective of the building committee: “The extreme height of the building up to the finial on the gables as shown in the design will be 288,’ 48 higher than the top of the Auditorium tower,” that had just been completed during the previous month (the added U.S. Signal Corps watch tower brought its final height to 275’). Once again, the challengers who were planning a taller building had waited until construction of their competition was completed so that it would be next to impossible to add extra height to compete with the planned taller height of their tower. The final design would comprise 20 stories to a final height of 302’-1.”

While the Chicago Hotel had given Root the opportunity to begin to avenge the loss in late 1886 of the design of the Auditorium to Adler & Sullivan as Root’s hotel rose four floors higher than that in the Auditorium, Sullivan’s 17-story tower was still the second highest structure in the city, overshadowed only by the Board of Trade’s tower, another lost commission and sore spot with Burnham and Root. As we have seen, when the 303’ (322’ counting the corona) tall Board of Trade tower was completed in early 1885, it was the first Chicago structure to be taller than New York’s tallest, the spire of Trinity Church at 281’ (though the Washington Monument still under construction was already taller than the Board of Trade). It was not coincidence, then, that on the same day that the permit to build the Chicago Hotel was approved, June 21, 1890, the permit to build the city’s tallest building (in terms of number of floors), the Masonic Temple, was also secured. Root, who had already designed Chicago’s first and largest skyscrapers, had his opportunity to finally avenge the loss of both of Chicago’s two tallest commissions. Note that I am limiting the Masonic Temple’s height title to only Chicago, because in New York, when the permit for the Masonic Temple was approved, New York had already reclaimed the title of the tallest building in America (and would keep it until the Sears, now Willis Building was topped off in 1973 and returned the title to Chicago.) The 305’ Statue of Liberty had overtaken Chicago’s Board of Trade, unless one counted Sperry’s corona that topped off at 322.’ Post’s New York World Building was quickly approaching its final height of 309’ (done on December 10, 1890), and construction of the tower for Madison Square Garden had already reached 304’ when it opened on June 16, 1890, with its ultimate height, including Saint-Gaudens Diana, still to be determined (for obvious reasons).

So I have always been perplexed by reports that refer to the 302’ Masonic Temple when it was completed in June 1892 as the tallest building in Chicago (it would not the tallest until the tower of the 303’ Board of Trade was demolished in 1895), or as the tallest skyscraper in the world (the 309’ World Building had been completed only five weeks after the laying of the Temple’s cornerstone), or especially those who claim that Masonic Temple had finally taken from New York the title of the tallest building in America. It was never the tallest building in the U.S., let alone the world, unless one defines tallest not in terms of its physical dimensions, but as having the greatest number of floors, which what must have obviously been meant at the time (for I know of no other building that had 20 floors, the World Building had 19). All these claims appear to simply be typical “Windy City urban legends.” Quite frankly, the matter was moot in less than two years anyway after the completion of the Masonic Temple, for the 348’ high Manhattan Life Insurance Building in New York designed by Kimball & Thompson with its own cupola, ended the argument (with the aid of Chicago’s self-imposed height limit off 1891) once and for all.

FURTHER READING:

Hoffmann, Donald. The Architecture of John Wellborn Root. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

Hoffmann, Donald. The Meanings of Architecture: Buildings and Writings by John Wellborn Root. New York: Horizon, 1967.

Monroe, Harriet. John Wellborn Root; A Study of His Life and Work. Park Forest: Prairie School Press, 1966.

(If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to eMail me at: thearchitectureprofessor@gmail.com)