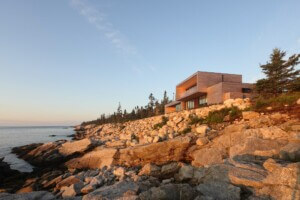

Summit Powder Mountain in Eden, Utah, is an ultra-exclusive community for billionaires with good taste. The mountain resort is a preserve for refined, and in some cases adventurous, residential architecture by the likes of Olson Kundig, MacKay-Lyons, and Studio Ma. The most ambitious and beguiling design comes from the Los Angeles–based office Tom Wiscombe Architecture (TWA)—an angular and withdrawn mass perching lightly on the downslope of the ski resort. The so-called Dark Chalet is a bit brooding, and one can easily see why the 5,500-square-foot home has been likened in the press to an “alien spaceship.” In most instances that would be a hack descriptor, but the project does indeed have the bearing of stealth bombers and sci-fi space cruisers. The house is nearing completion, so AN caught up with TWA founding principal Tom Wiscombe to discuss what implications it may have for his practice and for architecture beyond.

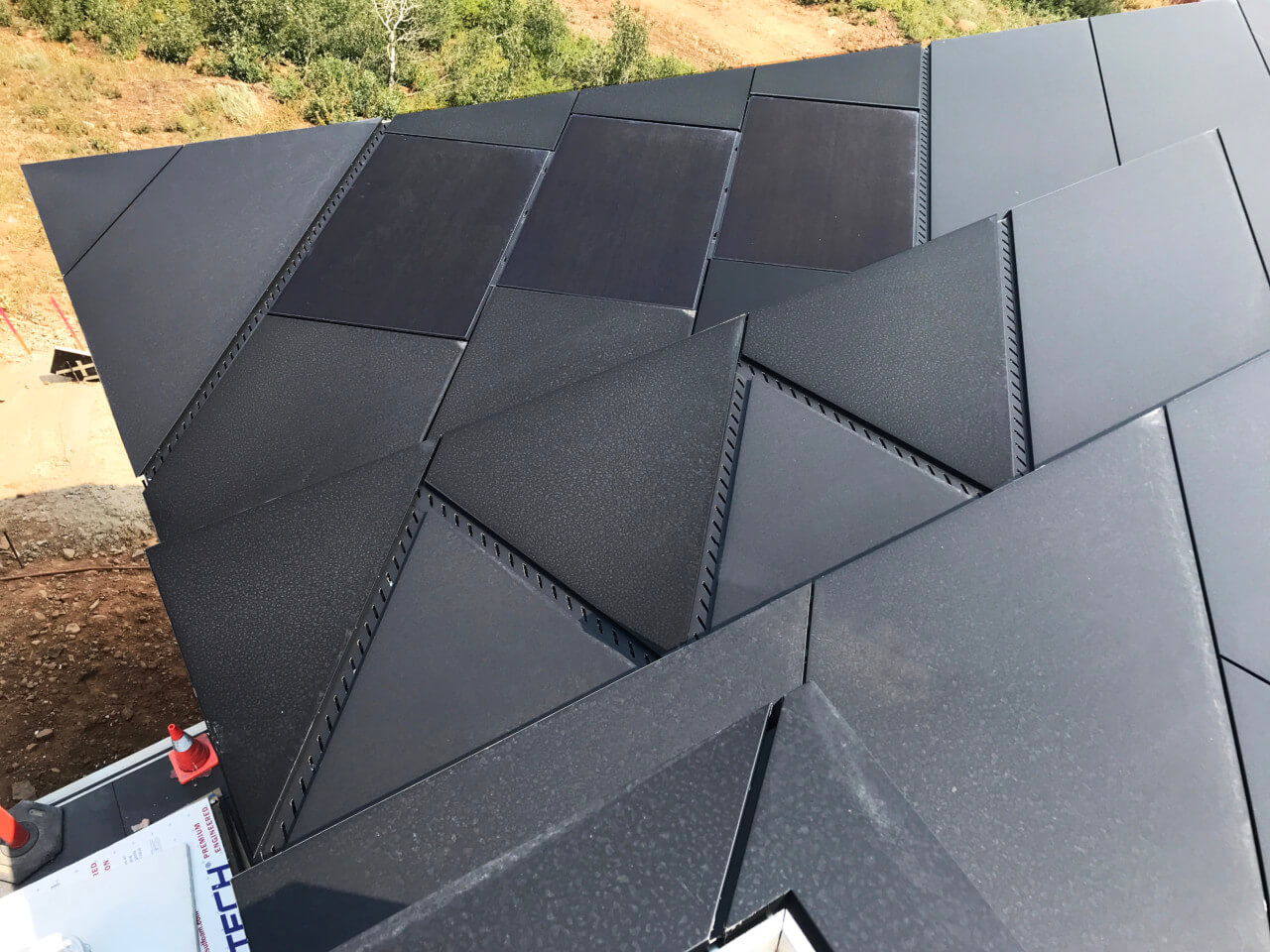

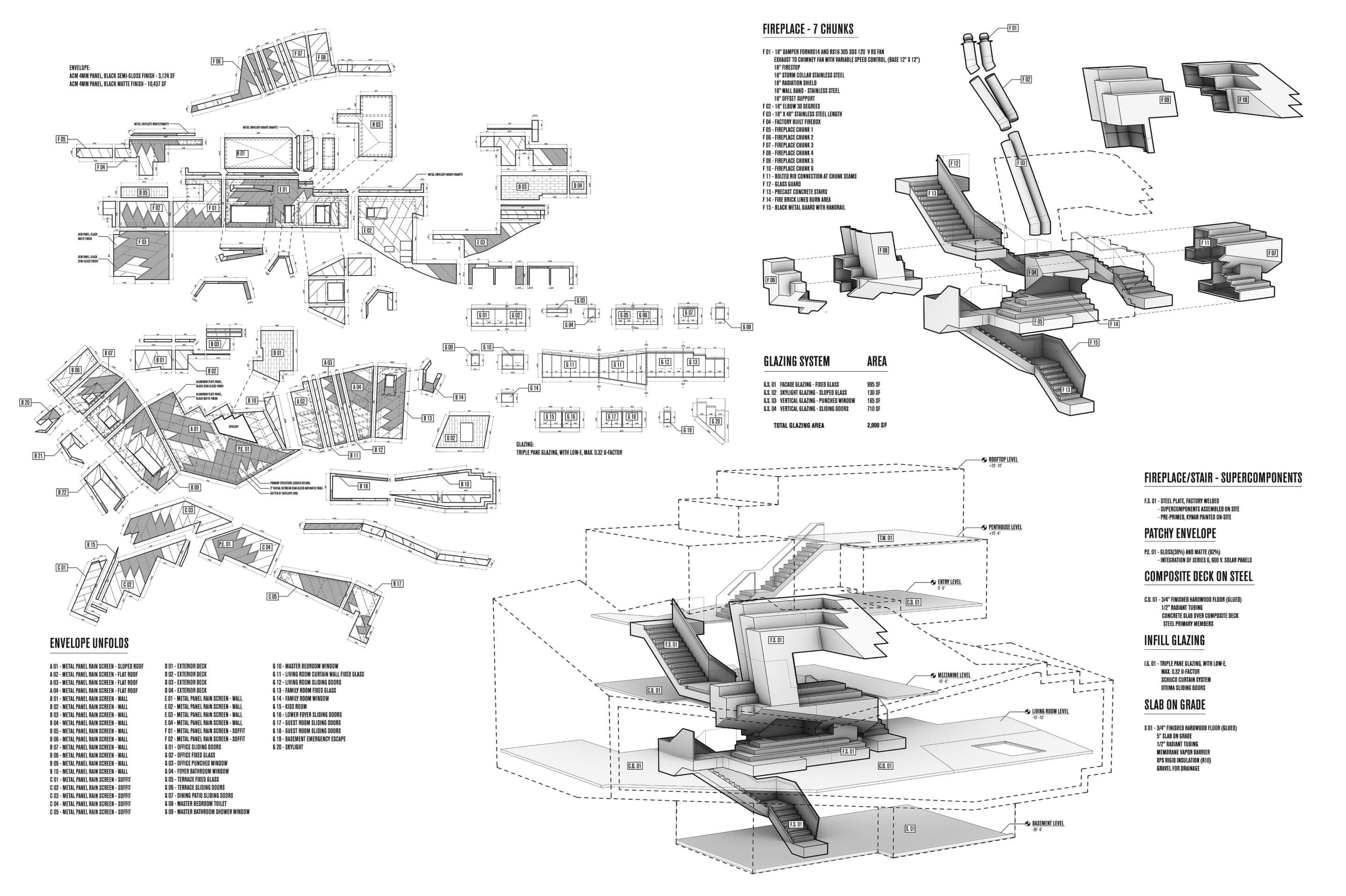

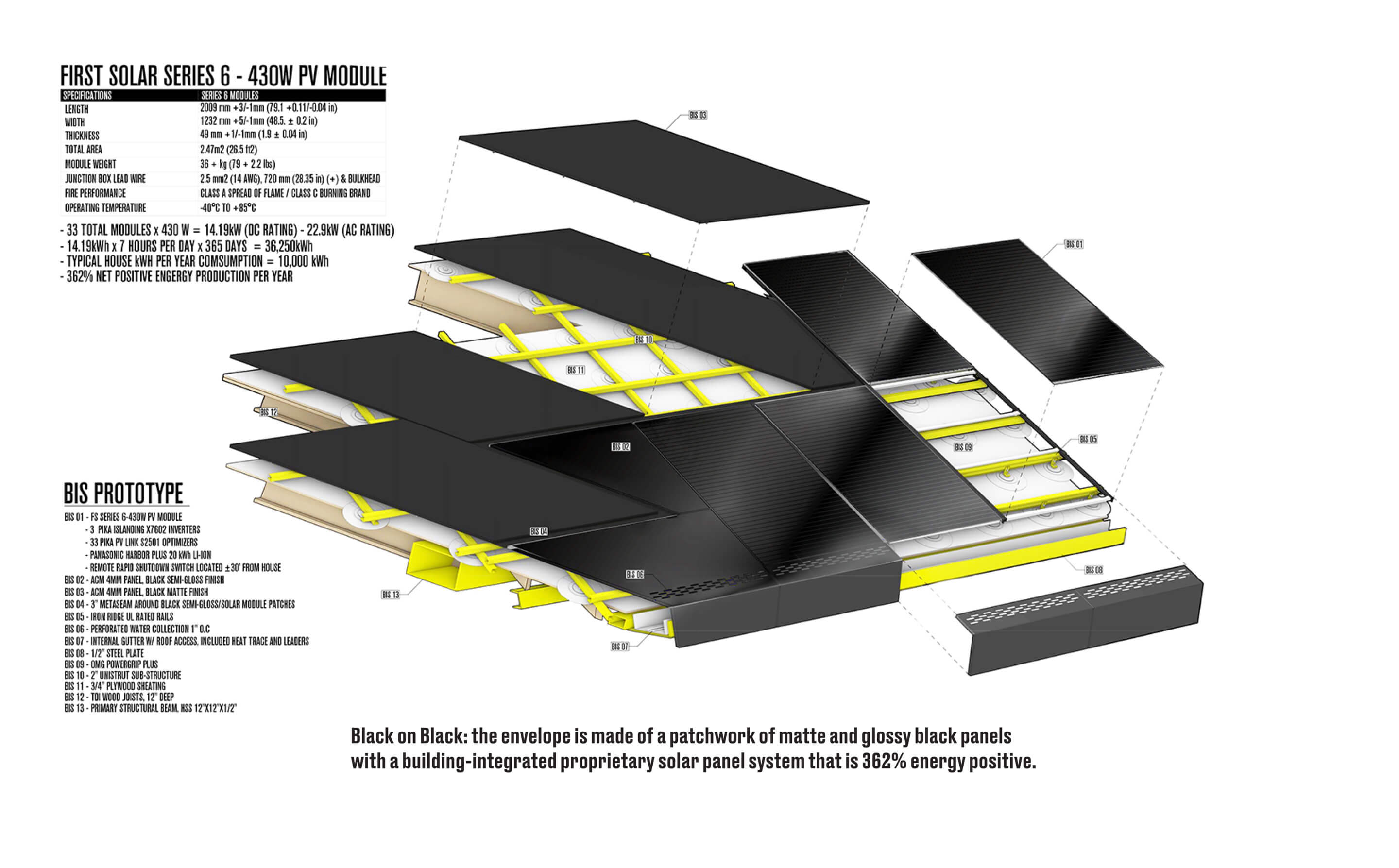

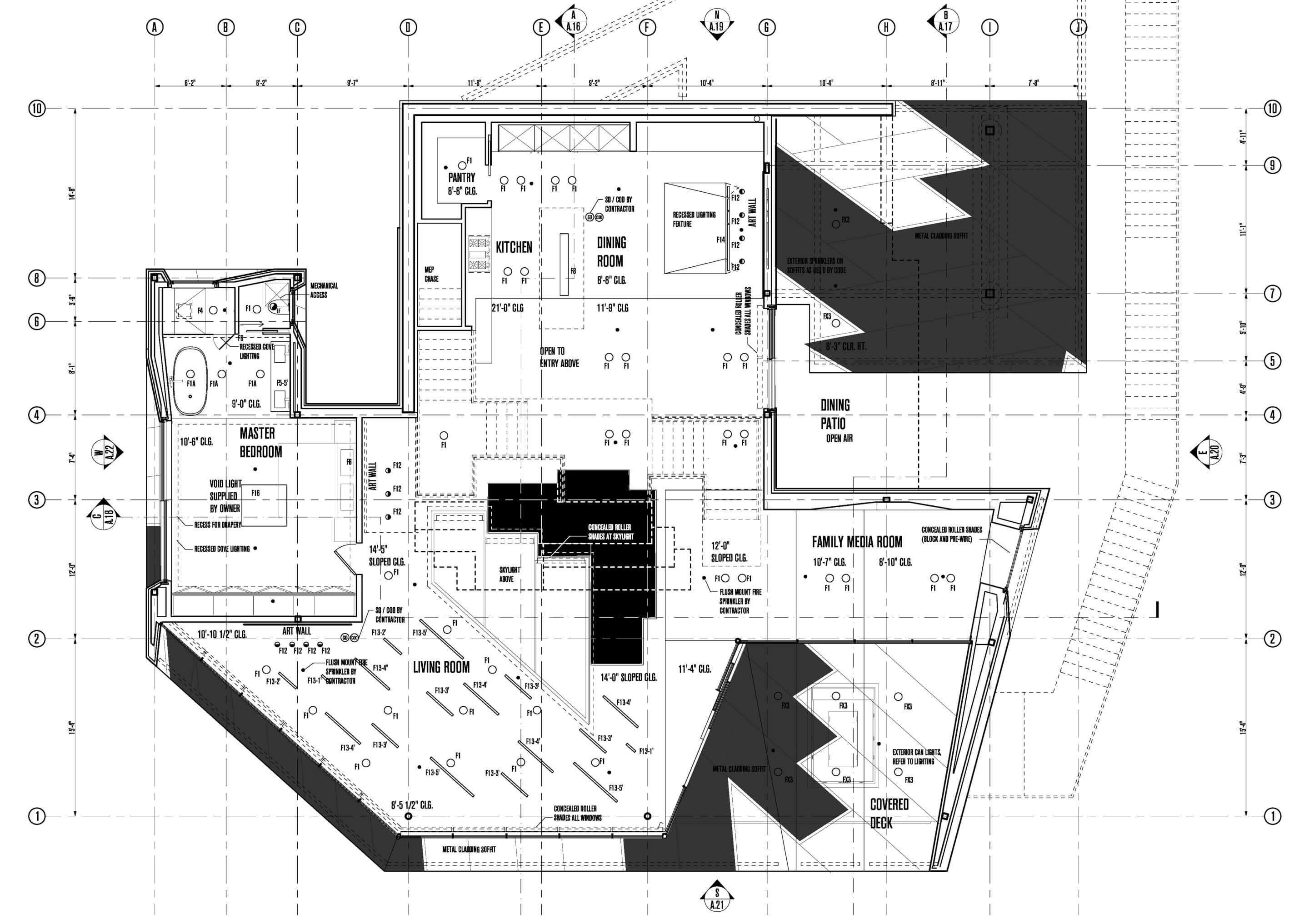

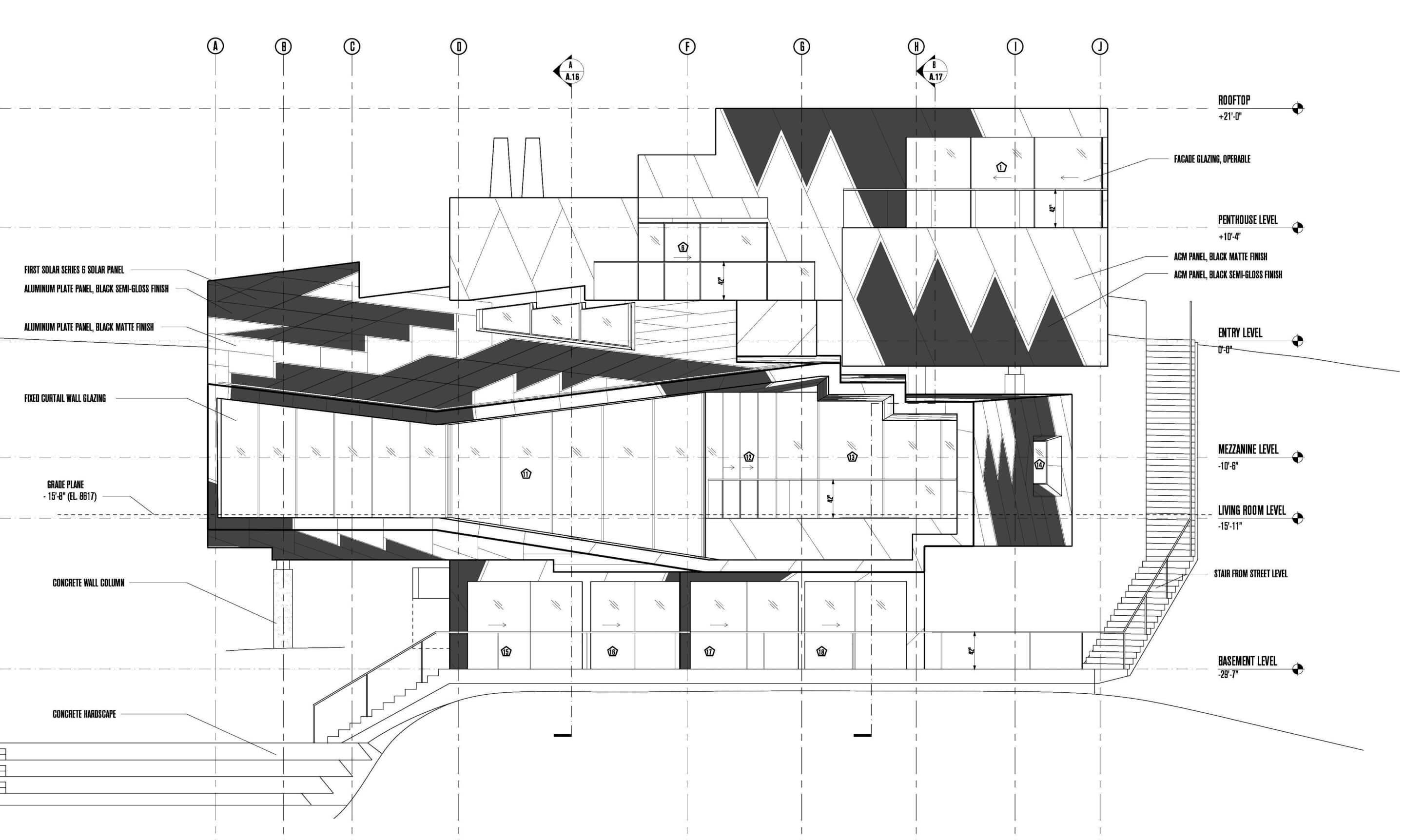

The Dark Chalet’s signature aesthetic is defined primarily by its “black on black” cladding, which had to be algorithmically segmented into jigsaw pieces to accommodate the house’s jagged, gem-cut form. The facade assembly comprises matte and glossy panels; the former are aluminum composite, while the latter are commercial-grade, integrated photovoltaic panels finished in black glass. The other standout feature can be found inside, where a massive central fireplace, itself embedded in a sculptural staircase, organizes the living spaces. Emblematic of TWA’s interest in nested geometries and objects, the fireplace has a presence somewhere between rarefied and alienating. “It’s weird because while [the hearth] ties all the levels together with the circulation and puts a fireplace in the living room—things you’d expect are going to happen in a house—when you’re in there, it feels like this separate entity that’s not totally fused with the rest of the house,” Wiscombe told AN.

The fit-out is nearly finished, and already the Dark Chalet marks a major milestone for TWA. Wiscombe chairs the undergraduate program at the SCI-Arc, the progressive L.A. school known for pushing the limits of form and technology. Prior to that, he enjoyed a long stay working at Coop Himmelb(l)au in Europe; returning to the United States, he set up shop under his own name and began churning out design proposals or competition entries. But he realized very few of these designs. That isn’t a criticism. Speculative architecture is incredibly meaningful for architecture’s image-based culture, and TWA’s work has for years been at the forefront of conceptual approaches to context, energy, and the objectlike nature of buildings.

But Wiscombe maintains that he’s not satisfied or interested in ending with the architectural image: “As an academic, I notice more and more a break between ideas of what architectural representation is and how we build or what construction documents are. I guess I’ve become tired of that. Anything that draws our architectural eye back into ideas about landing things on the earth is the sweet spot for me.”

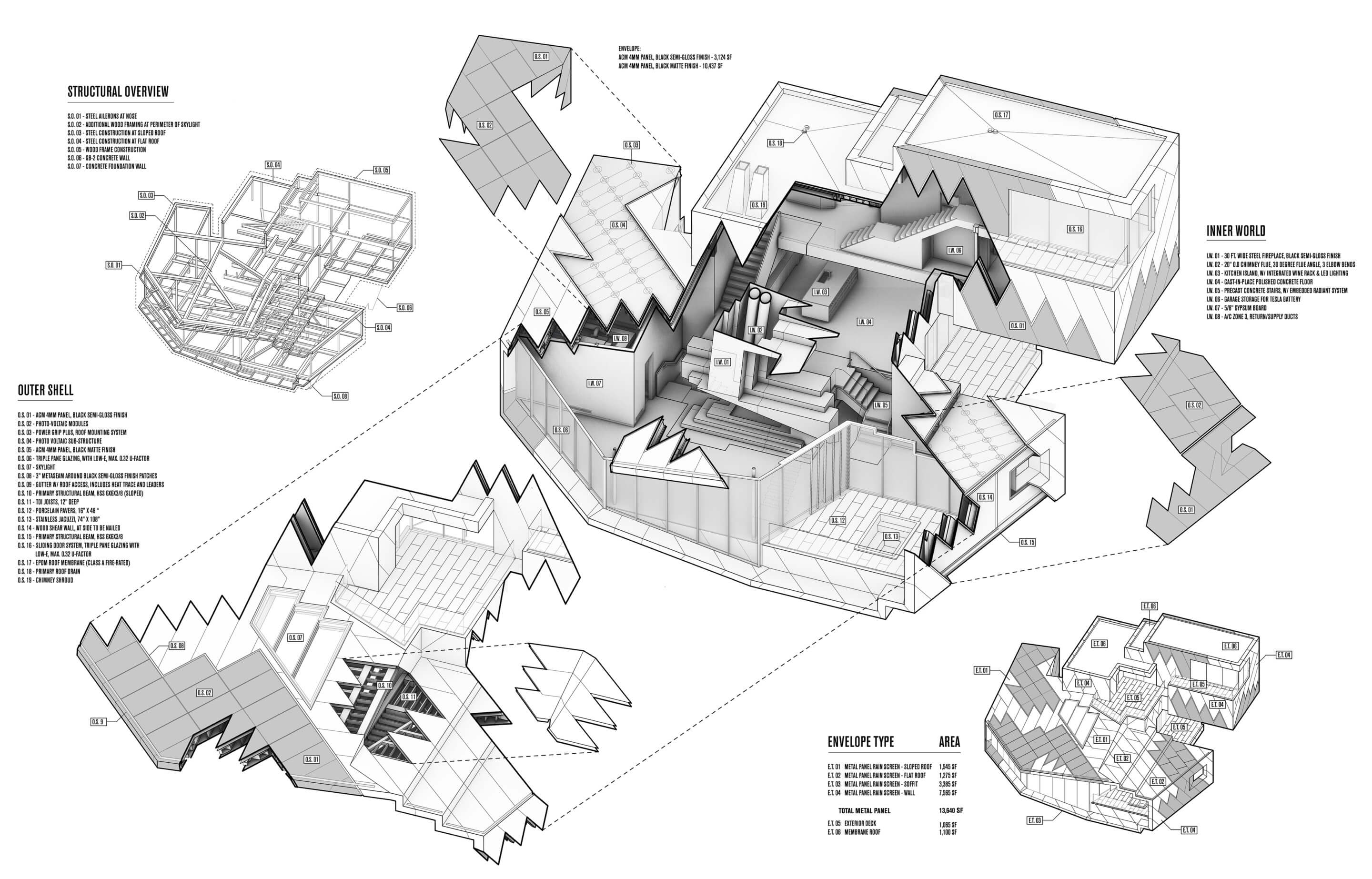

“Landing on the earth” is something the Dark Chalet certainly does well. While the project raises many intriguing theoretical questions, the more interesting story tells of highly practical issues of documentation, representation, and construction. In an unorthodox move, TWA assumed responsibility for much of the modeling, detailing, and issuing fabrication files for the complex facade. This involved creating an original design model in Rhinoceros and then drone-scanning the entire shell of the substructure on-site once it was waterproofed, which resulted in an updated point cloud model with tolerances within about one-quarter of an inch. Once TWA had this model in hand, the designers remodeled the details of the facade again—“basically what you would do if you were a facade contractor,” Wiscombe said.

Rhino and other modeling software can already facilitate some kind of design-to-fabrication process with CNC-routing and other tools, but applying that model at the scale and scope of a building, with its different trades and stakeholders, is no easy task. By taking over the fabrication files, TWA broke with convention, according to which the architect is responsible for design intent only, and the means and methods of construction or fabrication are the province of contractors and their subs. Wiscombe said he was aware of the risk his team was taking by flouting precedent, which has litigious implications: “As architects, we’re always trying to stay in our lane, [but] if we’re really invested today in integrated ways of building, I just don’t think that we can do that anymore,” he said. The risk paid off at the Dark Chalet, where the metal panels and PV array, with associated substructure and power supply, flush together perfectly. The resulting facade anticipates producing 364 percent of the house’s annual energy usage.

TWA also upended the look and use of construction documents, which cut up a building into thousands of flat, isolated moments. For Wiscombe, the ideal CD set is “the Revit file and a ‘Godzilla’ drawing or five ‘Godzilla’ drawings or however many are necessary to represent the full picture of the building so that ‘everyone gets it.’” His “Godzilla” drawings are dimensional cutaway diagrams similar to those packaged with Japanese toys and model-building kits, which detail the integration of exterior, interior, and in-between systems in a single drawing. While Wiscombe appreciates their striking and unique aesthetic atypical of architectural construction drawings, which tend to be quite utilitarian and convoluted compared with presentation drawings, he stressed their practical utility.

“I’m just always looking at drawing sets, and I just don’t like [them]. You’re not giving an overview of what we’re trying to come together as an integrated group to build,” he said. Instead, he wants to protect the “object” of his architectural desire: “Don’t hurt it. Be kind. Show as many of its features as you can, inside and outside, simultaneously. [You] therefore also give everyone access to it, from the plan checker to your builder to your owner—everyone gets it when you draw like that.” Although Wiscombe admits his office didn’t quite get to that ideal drawing set with the Dark Chalet, it got far enough to achieve a successful proof of concept. (The team achieved something similar—albeit at a smaller scale—with the interactive Sunset Spectacular billboard in West Hollywood.)

Still, there remain concerns about the project’s surrounding context. The Summit Powder Mountain development was dreamed up by a group of mostly white tech CEOs and venture capitalists who get together to talk about climate change, antiracism, and income inequality at a private resort where their vacation homes function effectively as tax havens. Asked about the political irony of this situation, Wiscombe pointed to the indirect nature of architecture and aesthetics. He cited the incredibly strict and conservative design guidelines that Summit placed on all buildings in the community, which TWA challenged in a number of ways, not least aesthetically.

“What is ‘mountain modern’? What is ‘heritage modern’? What do all these words mean?” Wiscombe said, in reference to Summit’s self-description. “What I’ve found out in talking with them is it’s not clear. It’s very vaporous what it includes and excludes. I hope that I put a bunch of big question marks in terms of the answers to that.” He’s grateful for his clients and the chance to work on such a beautiful site, but he’s clear about not trying to make excuses. “What we do as architects is inherently political, but I don’t think we operate in linguistic politics, where we speak ideas through language and take positions that way. I think we’re doing it in a much more backhanded, sneaky mysterious way through our work.”

Davis Richardson is a senior designer at Overlay Office. He teaches at the New Jersey Institute of Technology’s School of Architecture.