Breuer's Bohemia

Breuer’s Bohemia: The Architect, His Circle, and Midcentury Houses in New England

by James CrumpThe Monacelli Press, September 2021

Hardcover | 8-3/4 x 11 inches | 248 pages | English | ISBN: 9781580935784 | $60.00

PUBLISHER'S DESCRIPTION:

The iconic twentieth-century architect Marcel Breuer was a prolific designer of residential architecture, which is often overshadowed by his early renown as a Bauhaus furniture maker and his large-scale projects. Breuer’s Bohemia surveys the houses he designed in Connecticut and Massachusetts from the 1950s through the ’70s, many of which were commissioned by a few culturally progressive clients—chiefly Rufus and Leslie Stillman and Andrew and Jamie Gagarin—who coalesced around him into a dynamic social circle. Included in this scene were prominent cultural figures such as Alexander Calder, Arthur Miller, Francine du Plessix Gray, Philip Roth, and William Styron, and more, marking a unique intersection of postwar architecture, art, and letters.

The publication of Breuer’s Bohemia coincides with the feature-length documentary of the same name by author and filmmaker James Crump, exploring Breuer’s explosive residential practice on the East Coast. Through original research and interviews, the voices of principal characters from Breuer’s circle and notable figures from the field of architecture help tell the story of Breuer’s collaborations with his friends and clients, breathing new life into the history of the rich cultural atmosphere of which they all played a vital part.

Heavily illustrated with vintage and contemporary photographs as well as rarely seen archival materials, Breuer’s Bohemia is a unique glimpse of a twentieth-century milieu that produced an aesthetic, intellectual, and sometimes sybaritic community during a fertile period of American design and culture.

James Crump is a writer, director, and producer whose films include the documentary Troublemakers: The Story of Land Art (2016). An acclaimed art historian and curator, Crump is also the author, coauthor, and editor of numerous books and has published widely in the fields of modern and contemporary art.

REFERRAL LINKS:

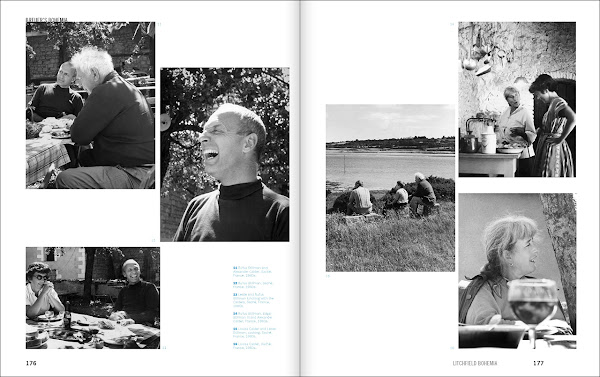

The latest film by James Crump, director of Troublemakers: The Story of Land Art and other documentaries, tells the story of a circle of friends and acquaintances centered on Litchfield, Connecticut, between the 1950s and the '70s. As the name Breuer's Bohemia attests, architect Marcel Breuer is the main subject, and the lives of his family, his clients, and the larger social circle is best described as bohemian, unconventional in both style and behavior. The modern houses designed by Breuer for the families of Rufus Stillman and Andrew Gagarin departed dramatically from the colonial and Greek revival houses across Litchfield, while the parties held in the numbered houses (Stillman I, II and III; Gagarin I and II) are described at one point in the film as "bohemian on crack." Attending such a party would have meant sitting next to, and having drinks with, famous artists, writers, actors, and even future politicians. It's a captivating story deserving of a companion book.

The main idea of Breuer's Bohemia, both the film and the book, is that the architectural talents of Marcel Breuer were nurtured and greatly expanded by the patronage of Rufus Stillman, who not only commissioned him for numerous houses, but also convinced other clients to hire Breuer for their projects, residential and otherwise. But before Stillman entered the picture there was Walter Gropius, a mentor of Breuer's at the Bauhaus in Germany as well as at Harvard University, where Gropius was chair of the architecture department and Breuer joined him as a professor in 1938. The two had a brief architectural partnership and built houses for each next to each other in Lincoln, Massachusetts (Gropius's is visible in the first spread, below). Although the film and book attest that authorship during their partnership was not always apparent, the Chamberlain Cottage in Wayland (1941) was certainly Breuer's work, and an important project that signaled his move away from Gropius and the start of his own practice in New York City.

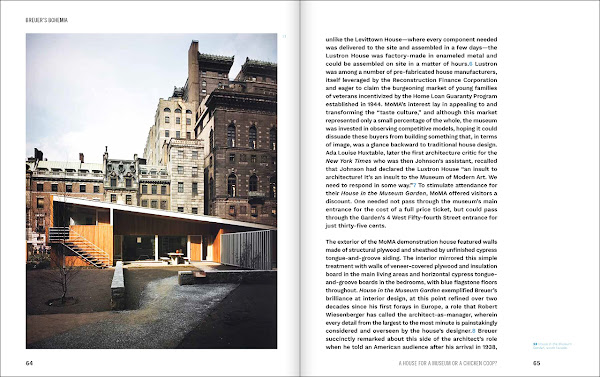

The next watershed work for Breuer, and the subject of the book's second chapter is The House in the Museum Garden, a 1:1 house built in the courtyard of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1948. With its distinctive butterfly roof and wood siding set against the stone-faced townhouses of 54th Street (second spread), the postwar house was clearly a dramatic departure from conventional houses in the United States at the time. One of the many people who visited the house during its six-month residency was Rufus Stillman, who supposedly determined then and there that Breuer would design a house for him in Litchfield. Cementing the decision was a visit to Breuer's own house in New Canaan, Connecticut, which was completed the same year as the MoMA house. While the film gives the impression that the decision was an easy one, the book recounts how Stillman had already promised the commission to John Johansen — one of the "Harvard Five" alongside Breuer, Landis Gores, Philip Johnson, and Eliot Noyes — but instead of burning bridges Stillman would eventually help Johansen gain other commissions in Litchfield. This is just one instance of many where the book adds depth to the stories told in the film.

The chapters that follow survey the cottages Breuer designed in Wellfleet, Massachusetts; describe the competitive relationship between Stillman and Andrew Garagin, another repeat client for Breuer; and recount some of the tumultuous relationships in the social circle centered in Litchfield. The film is structured into decade-by-decade "chapters" and the book basically takes the same chronological approach, moving from the diaspora before World War II to Breuer's death in 1981. Both the film and the book intertwine narratives of architecture with those of the social lives of the houses' clients, guests, and designers. Many books opt for one or the other, so Breuer's Bohemia is refreshing, even if an unspoken white male privilege undergirding the houses and the goings on within them seems out of step with contemporary concerns. Still, the very real specter of McCarthyism and bigotry over immigrants, and stories about atheism, homosexuality, and the progressiveness of Breuer's promotion of women architects within the profession help to situate the members of the circle as outsiders in their day united by a desire to make change. In both media, Breuer's Bohemia is an excellent, vivid documentation of a specific time and place, one that shouldn't have a hard time finding its audience.

SPREADS: