Collecting the stories, research and expertise of leaders in the material health field shared at a 2019 symposium, Material Health: Design Frontiers, published in 2022, is an invaluable handbook for architects and designers looking to cultivate a more responsible practice. Centering on Indigenous knowledge and strategies for living with and among the natural world, this is a fresh and grounding take on design innovation that goes deeper: an ongoing mission of the Parson’s Healthy Materials Lab’s co-directors Jonsara Ruth and Alison Mears.

If we imagine a built world created to support both people’s health and all of nature’s ecologies, environments, and living things, then we need to chart a path different from the one Western culture has forged.

Indigenous voices call attention to the importance of learning lessons from ancient cultures that have lived harmoniously with nature for thousands of years. Indigenous ecological knowledge challenges us to nurture, rather than extract, the planet’s abundant resources. Their regenerative practices support healthy places, and therefore healthy communities, for future generations. Within these Indigenous philosophies there is a fundamental understanding that our shared livelihood is all of humanity’s responsibility. Clean water, clean energy, fertile soils, and healthy, affordable homes for everyone are possible only through reconsidering and regenerating our human activities. What if this were the goal of all of today’s decision-makers?

We—Alison Mears and Jonsara Ruth— cofounded Healthy Materials Lab (HML) at Parsons School of Design in New York City to address these intersectional issues related to designing the built world. As women educators, architects, and designers, we pursue our goal to raise the design and construction bar in housing to provide truly sustainable, healthier, and beautiful housing for everyone.

The problems of climate change and human disease are inextricably linked, and based in large part on carbon emissions. Our work has focused on the field of material health, an ecosystem-first approach. Our work at the lab seeks to understanding the toxic life cycles of common building products—from the mining of raw ingredients to their refining, production, and installation processes. We then move forward optimistically, entering into the discourse and research surrounding emerging circular systems of material reuse. In our recent publication Material Health, we consider these and posit critical points of disruption.

HML works to create a truly sustainable architecture, engineering, and construction industry. We demand ingredient transparency and advocate to reduce embodied carbon levels in the building product supply chain. Our work goes beyond individual materials or bespoke projects, aiming to influence the industry at scale.

To make change possible, we provide resources to architects and designers so that they can put human and environmental health at the center of all design decisions. Our recent book Material Health Design Frontiers is the outcome of a conference we hosted in 2019, which focused on six themes: air, carbon, equity, ecosystem health, circularity, and ultimately design innovation. Thanks to our 19 expert contributors, including a toxicologist, a pediatrician, environmental justice advocates, materials innovators, artists, architects, and designers, the essays describe many positive ways to change the way we live and build.

Forefronting design examples with a description of the issues that need to be addressed, these case studies show that it is indeed possible to shift the way we conceive of the design process and the way that has become the conventional construction process.

Our work at HML remains firmly rooted in practice. No content remains purely theoretical. A healthy relationship between the natural world and humanity is fundamental to sustaining and supporting human life. It is time to reject the historic and extractive dualities in Western culture between nature, culture, mind, and body, because they isolate us from the essence of what makes us human and disconnect us from all other species. A new innovative path for decision-making is possible. We need positive, radical collaboration at scale, and the built world will evolve into one that is regenerative, just, healthy, and prosperous for many generations to come.

This change is imperative, and the time is NOW.

Air

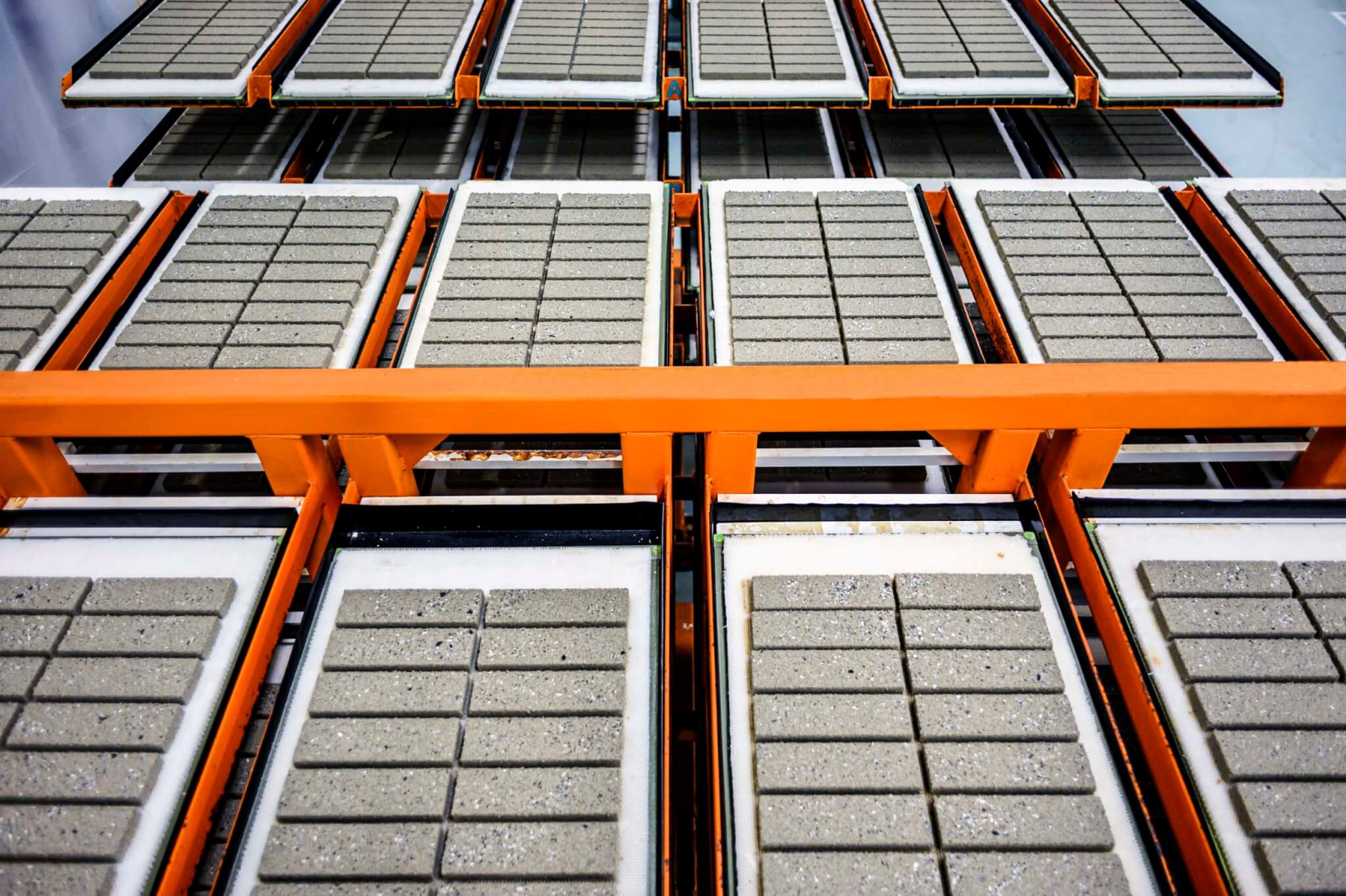

The opening chapter of Material Health focuses on the air we breathe—a shared resource that knows no borders. Air quality is a key indicator of both human and environmental health, yet these collected studies here show how the two are inextricable. Laura Vandenberg, a biologist and professor at UMass Amherst, focuses on the distinction between toxic and natural chemicals in our environment; Aaron Dorf, director of Snøhetta U.S. discusses the ramifications of the phrase “healthy materials” for practicing architects today; and Ginger Krieg Dosier, architect and founder of Biomason U.S. discusses how material exploration is, and can, disrupt the construction industry.

Carbon

The case studies and products explored in the Carbon chapter of Material Health are visually arresting: they playfully present cutting-edge research in forms that are beautiful and often even engaged with pop culture. Items like a new sneaker designed by Adidas appear; the Futurecraft Loop Shoe is made with recyclable Thermoplastic Polyurethane. Also, a designed experiment titled Air-Ink is presented like a tempting Instagram ad: Different plastic containers resembling paint pens, jars of ink and brush marks contain a silky black liquid. What we read as “paint” through this graphic is actually particulate carbon matter ink, dyed with the particular emissions of 19.6 hours of diesel car pollution.

Equity

Environmental justice has emerged as a powerful movement in architecture and design circles, asserting that without equal access to clean, healthy environments (and buildings) we cannot claim to reach equity and inclusion goals as a practice or as a society. Collected essays in this Equity chapter highlight the work of Dr. Maida Galvez, whose work as an environmental pediatrician challenges traditional labels and offers “prescriptions” for healthier buildings. But equity in quotidian workplace culture is also explored. Samantha Josaphat-Medina reflects on job (in)security in the AEC profession, particularly for marginalized groups, unpacking the feeling of being “stressed behind the desk,” and she’s not alone.

Waste and Circular Economies

“Take-make-waste” is how Kate Daly, who directs the Center for the Circular Economy at Closed Loop Partners, described our current economy and patterns of consumption. And while there are many calls for regenerative, non-extractive systems, these are difficult to realize, or even envision, within the current capitalist system we find ourselves in. Circular economy as a phrase in the AEC industry relates often to material flows and recyclability at the end of a building’s life, emphasizing that the end of a building need not be the end of a material. But even small steps like this are parts of a larger financial, economic shift that Material Health scrutinizes in this chapter.

Ecosystems

“The use of so much plastic was by design. How could we have been so misguided?” asked Franca Trubiano, practicing architect and professor at UPenn. When we think of ecosystems as the concluding chapter of Material Health, it challenges us to think deeper and zoom out. What is a measurement or a certification if the building (be it net-zero or LEED platinum) sits on a foundation of polymers and fossil fuels? Holistic perspectives as well as holistics applications of data and method are necessary if we want to make meaningful change in our built projects, as practitioners like Henning Larsen are advocating for in this section. We can’t just unlearn, we must work toward new systems of practice and understanding.

Alison Mears and Jonsara Ruth are the cofounders of the Healthy Materials Lab. Jonsara is the design director and Alison is the director.