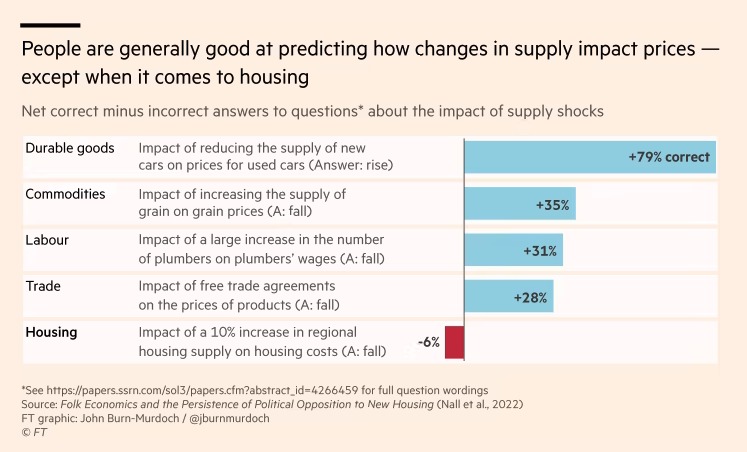

Here is a study by three researchers out of California that asked Americans to predict the impact of a supply shock on various things, such as durable goods, commodities, labor, trade, and yes, housing.

For basically all of these items, people tended to answer correctly. Usually by a factor of at least two to one. In other words, when asked what reducing the supply of new cars would do to the prices of used cars, the majority of people responded saying that it would lead to an increase in prices.

However, when asked about the impact of a 10% increase in housing supply, about 40% said that it would cause prices and rents to rise. Only about a third believed they would fall (the correct answer). This is fascinating because it shows that housing seems to be an outlier. Most people don’t have the same intuitive sense.

Why is this? Well, one commonly held belief is that building market-rate housing leads to gentrification, and that this ultimately leads to the displacement of existing residents. This might have been why some people responded saying that new housing will cause an increase in prices and rents. It’ll lead to all housing going up.

However, there’s research to support that this isn’t the case. The problem isn’t outward displacement following new market-rate housing. The greatest driver of gentrification is actually “exclusionary displacement”, which is the inability of people to move into areas because of a lack of housing. (This study was based on 2010-2014 housing data from the UK.)

The thing about housing supply is that it relieves pressure across the entire market. Instead of a high-income person buying an old home to renovate (and causing outward displacement), they can instead choose to buy a new home (and not cause any outward displacement).

By doing this, they also leave behind a home that can then be absorbed by lower earners. One US study found that for every 100 new market-rate homes that are built, somewhere between 45 and 70 people move out of a below-median income neighborhood.

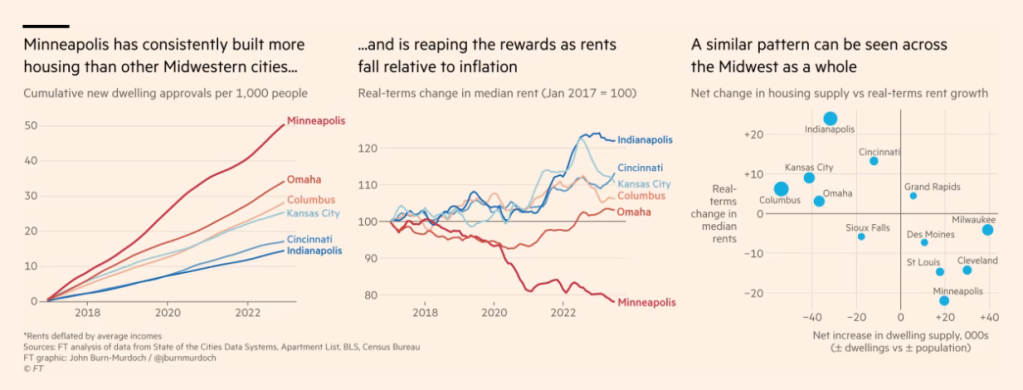

It is for reasons like these that, time and time again, increased housing supply has been shown to moderate home prices and rents (see above regarding Minneapolis and the Midwest as a whole). So if you’re worried about the cost of housing, the answer is to build more. And if you’re worried about gentrification, the answer is also to build more.

Our intuitions are telling us that this is true for most things. But for whatever reason, housing feels different. It’s not, though.

Source: The charts and studies in this post are from this great FT article by John Burn-Murdoch.

Would the impact on a local housing market also fluctuate based on the type of housing (luxury vs. Affordable vs. Social housing) being added?

Also interesting is why Canadians generally see the benefits of universal health care (everyone needs access to healthcare…duh) but don’t draw those same conclusions when it comes to housing. Housing being delivered by the private market is equally as flawed as privatized health care; benefits are only available to those who can afford it.

LikeLike

Because the correct answer is that housing is different and the people who answered that more supply does not automatically make prices go down are correct. That’s due to external factors which do not apply to other goods. For instance, the impact of land lift, building and marketing to investors… These things don’t happen with, say, bananas.

If you flood the market with bananas, they go down in price. We have seen record building in Vancouver. Which way have prices gone? How do interest rates impact bananas? Are there limited banana workers which drive up production costs? What do developers do when prices are falling? The answer is, they stop building. Most developers only want to build in rising markets, not falling markets so if the impact of more housing is to do that, developers are not interested. Banana growers, on the other hand, don’t stop growing bananas because prices are lower.

And what if you supply mostly very tiny bananas and most people strive for large bananas? What happens to the price of limited, but very sought after large bananas? Does more supply of small bananas make large bananas fall in price or go up? If the land used to grow those large bananas gets used for growing small bananas, even less large bananas are produced which, of course, makes them even more expensive, not less.

That’s why the premise of the article is incorrect.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is the comment I would have wanted to write, but you did it much better than I ever could.

Both Brandon’s article and this comment raise, imho, is how to make developers keep building in an environment where profitability is falling (due to lower sales prices).

Brandon’s answer to that is, let’s reduce cost for developers, so they can build more projects that otherwise wouldn’t have been built in the first place because they don’t make financial sense. One can argue that, while not lowering prices, this would at least keep them from going up much faster.

This still doesn’t answer the question of how to make a developer price their projects lower than previous ones after all the price increases. I mean okay, temporary incentives yada yada, cashback and whatever, but like other industries there’s a huge incentive not to make the actual sticker price come down. In good times, increase profit margins. In bad times, build less to preserve profit margins as good as possible. It seems to me that the entirety of price drops would be coming from existing housing stock dropping, while new developments will, at best, not raise prices any further and instead just tweak volume.

In order to really make prices come down, I feel like it’s necessary to force a certain number of developments being built, so that prices become elastic rather than new supply. From that point of view, I like the idea behind “use it or lose it” kind of legislation, even if perhaps the execution of this current iteration leaves something to be desired. What’s missing is a backstop that takes any unused land and puts it in the hands of someone who can do it cheaper. Part of this could be a government agency, not because they can build more efficiently, but because if they can’t, the government would eventually notice and do something about the reason that blows up the backstop development costs i.e. budget deficit.

A fully socialized housing would be terrible, but maybe the entire sector could benefit from some actual competition between government (focused on lowering margins and increasing supply) vs. private developers (focused on preserving or increasing margins while being conservative on supply).

LikeLike

We’ve already seen prices come down in this current environment:

– There are condominium launches today that are at least $100-300 psf less than where they would have been at the peak.

– There are launches today where the developers are trying to move forward with razor thin margins just to keep the lights on and their teams employed.

– My own view is that many of the launches expected this fall will not be successful. In other words, there’s far more supply in the market today than there is demand.

As expected, this has pushed down prices.

LikeLike

A more accurate statement would be that many/most developers “can’t” build in a falling market. If you employ a large team of people whose job is to deliver new housing, you want those people building new housing. Paying them to sit around and not build is a problem.

Tiny vs. large — this is another debate that we have on this blog: https://brandondonnelly.com/2023/06/03/everybody-wants-a-3-bedroom-condo-until-they-see-what-they-cost/. Developers build what the market wants.

LikeLike

“Developers build what the market wants.”. This is the whole issue though, right? For developers, the market is foreign and domestic investors who buy units by the handful and then either rent them out, or leave them sitting empty. We see this in Vancouver and the rents for new condos are not cheap at all, so they are serving just one market. Developers actually don’t build what the market wants, they build what is most profitable for that segment of the market.

And if developers cannot build in a falling market, then how do you suppose we get supply to cause prices to go down? You’ve just confirmed here that when prices are falling, the market responds by not building, so it’s an endless loop of building while prices are increasing and not building when they are falling. That’s precisely why the notion that building more will cause prices to fall is just not true, but you seem to be confirming it yourself.

You say there are condos today which are selling for less. That’s a response to interest rates, not more supply. The supply factor has nothing to do with prices falling and if interest rates started dropping, the market would rebound and prices would accelerate again. This is how it works.

Interestingly, in Vancouver the city removed the “burden” of the empty homes tax on new builds because developers lobbied. They have the units built, but they don’t want to sell them at market rates today so they want to be allowed to keep them sitting empty so they can wait for prices to recover. They sit empty!! And now with no tax penalty, they are not penalized for doing so. The notion that prices will fall is shown to be false as here, prices remain high and units sit empty. Again, this is how it works. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

LikeLike

The data is clear if you read the article. Lots of supply brings down prices. It’s not a single project or a few projects that get the job done. It’s a long term ongoing oversupply that finally will get prices moving down – look at the Minneapolis data above. Too many people, politicians included, want to try and fix the issue (that was decades in the making) with the next project that is built (80% market , 20% affordable). The reason homes were affordable in the 70’s and 80’s was that lots of supply was built over the decades post war 1950-19070s. No one was “forcing” developers to build what the “market needed” back then. What we need is cities to get out of the way – approve faster, reduce all of the taxes in the process and let the market get to work. Even if we do that the correction will take years if not decades.

LikeLiked by 1 person